$1.3bn - $2bn for a 9% up to 40% chance to save 1.2 million US lives earlier

$700m, 9%+ chance save 200,000 UK lives

Make a significant investment to scale up current vaccine trials

Chance mass vaccinations once safety data is passed

Chance mass antibody protections? Accelerate treatment trials.

Flatten the curves maths uncertain, vaccine and treatments good bets in any scenario.

Treatment/trial protocols should be set up now and accerelated after positive safety before full phase 3 trials

Please also see end disclaimer and draft open letter on this idea.

Is it not possible to have a vaccine into the field in 6 to 12 months, rather than 18 to 24 months?

I think it should be with some money ($1bn to $2bn), will power (some companies will have to work hard) and a change/boost from regulators (typically they’ve not allowed drugs on to the market until definitive efficacy is shown, though have in certain cases eg cancer, as they are risk averse) . I don’t even think incentives need to be changed much in this case, although a re-think here would help for the future.

My proposal:

-start mass scale up of leading vaccines now

-if safety trial is positive (April we might know but there should be some data already available)

-then proceed to vaccinate the 60m elderly in USA

If safety trial has passed this has in the range of a 20% to 40% chance of working (my estimate). Note, BIO suggests 24% success for a phase II vaccine and 16% for a phase I vaccine.

Best case scenario: 1.2m+ lives saved

Base case scenario: no change, $1.2bn spent but manufacturing technology and other assets built

There is no worse scenario if safety has passed except for tail events and resources used. I guess small chance that somehow this messes up a future vaccine,, but seems unlikely.

Getting 60m vaccinations is tricky but they can also get the flu shot at the same time which should prevent flu deaths in any case.

Details:

Moderna has already submitted a vaccine candidate using its mRNA technology. It’s currently being tested in safety trials. There are several other vaccine candidates, (cf. Inovio, Sanofi, J&J, GSK) but the speed is too slow - and it might not need to be this slow.

There is time and money needed to scale up manufacturing in case of success. This could be accelerated for $500m, if started now. That investment could be used to negotiate, say, a $15 price for the vaccine. CDC pays $18 for a flu vaccine.

So ball park for US that would be a $1.4bn investment.

While the UK has only 12m elderly, maybe it could go halves with the US. Still the same calculation for UK is about $700m.

Note, CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) has suggested $2bn for for up to 3 candidates to go forward finally past phase 3 (starting with 8 or so in phase I). So, about $1bn for one drug seems doable, at speed. Now the mostly traditional system, will have a good probability of success but it will be slow. So I’m suggesting a $1bn, 6% chance bet on one or 2 candidates now, for a chance for a vaccine in 6 months - that’s 12 to 18 months before the likely CEPI process. (We also know with some recent fast success in cancers. cf. Roche, Merck PD-1s, Novartis’ Gleevec some of this is possible at speed)

I’m also suggesting we allow drugs once they pass safety (or have passed safety), to be allowed into the field (this would cover Regeneron’s possible treatment, it would cover Chloroquine, baricitnib and ruxolitinib - these have already passed safety in other indications; it would be resmedivir as well)

Source: Regeneron (Cowen Conference, March 3)

Also, note there might be antibody treatments - this would be Regeneron’s approach. It won’t have antibodies ready until summer, but once ready, after a short safety trial, it might be worth going to dose the elderly. So say doeses ready in August, safety trial Sep - get it ready now - and start dosing in October. This could be expensive but only in the order of $2bn to $8bn depending on price. Now, in October we won’t know efficacy, but if safety is basically clear, then again we have a 20 - 40% chance of success albeit at a higher cost (as antibodies are more expensive).

Vaccine probablity of success

Vaccines have a 6% percent of success once in pre-clinical trials (base line stat) and around 16% when in phase I. Investors use a range of 1% to 16% chance of success typically for Phase I drugs. Risk is often bucketed for (a) safety (b) efficacy and c) regulatory.

There are plus/minus reasons to vary the risk of a COVID vaccine. Regulatory risk is lower than average. Reasonable people can argue for safety/efficacy risk. The mRNA technology is new, but we do have the virus genome. We know how to make flu vaccines very successfully, so it’s proabably a matter of time and investment rather than completely new invention/innovation needed.

In any event, this is a >0 success rate, and a ball park 9% is reasonable for a novel phase I vaccine.

Vaccine and treatment idea details

Manufacturing in advance. This needs to start now as scale will be needed.

Trial for efficacy now. Ask for volunteer elderly, maybe healthcare worked and start the phase 2/3 test immediately in April/May. This is if you simply can’t push through vaccines when not yet tested.

If you scale up the money, you can run it on all 8 or so most viable vaccines, $8bn should be enough to take through an accelerated phase 2/3 + manufacturing if there is regulatory and company willing.

There are 80 or so drug treatment candidates identified by WHO. (see sources end)

We should start with drugs already approved and get them ready for trial in the field.

This would include chloroquine (already being used by China) and baricitinib (as identified by AI processes), China is running trials using ruxolitinib. These are treatments rather than preventative but still useful in curing patients and getting them out of ICU.

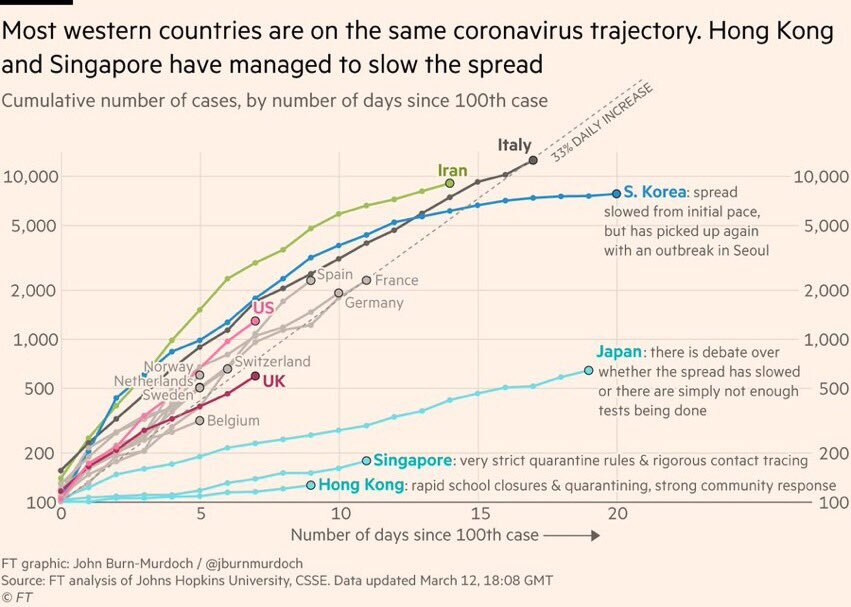

The practical maths of flattening the curve

The UK needs to keep ICU cases down to approx 1000 (range up to 2000). This means peak diagnosed confirmed cases at 20,000. (Range 10K to 40k). The measures required to do this in the UK given current doubling times are have quetionablt in feasibilty Some modelas have. UK reaching 20,000 cases between 21 to 90 days. And an ICU case may stay in ICU for 3 weeks+ depending on death or recovery. So keeping capacity at the ICU level is going to hard. We may be able to produce cheap ventilation and free up capacity, but it might be tricky.

That’s why accelerating a vaccine and treatments are a good bet, as they might help get in before the peak or help people out of ICU.

Tough maths of elderly deaths

Let’s look at some other brutal maths. 1 year or 2 year infection rate estimates might range from 20% to 70% of the population. Swine flu had a 20% infection rate and 150K to 575K people died (CDC data). Swine flu also circulates every year now since 2009.

A 20% infection rate seems very plausible. The case fatality rate (this is for when you are assigned as a case and so doesn’t include non-symptom or mild cases that don’t get reporting) is very hard to know.

These are the brutal maths for the UK and Italy.

Italy has about 60m people and >22% are over 65 —> over 12m elderly.

If 20% are diagnosed —> 2.4m and at 4% CFR —> 96,000 deaths. It’s easy to see how this might range up to 200,000+ easily with double diagnosis/CFR.

In the UK, it’s about 18% of 67m —> this is also 12m elderly. The maths is the same, if 20% are diagnosed —> 2.4m and at 4% CFR —> 96,000 deaths.

Politics of this bet

In UK, US many conservative / Republican voters are elderly >65. There are more of these Rep voter >65 (and this reverses for under 30s).

So in particular for Trump and Johnson, this would be a political calculus to consider if they wish.

Alternatively, some have argued that losing “unproductive” >65s might make for a more productive economy with lower social cost burden. Eeek.

The Future:

Pandemics are very likely (over 90% chance) to occur (again) over the next 50 years and likely over 100 years+ time frames. This pandemic was predicted by pandemic experts.

This is because:

-humans are increasingly interconnected at speed

-the way we treat/breed animals is not changing any time soon

-wet markets and similar not likely to change soon (though I think in eg China there will be a crack down)

-current viruses/germs eg influenza, pneumonias have been around for 1000s years

-virus/germs will constantly mutate

-containment will slow, likely never stop, transmission

What to do about future pandemics

-cultural learnings eg greetings

-innovation

We can slow transmission and in small cases potentially even stop by a change in cultural norms. We know the behaviours - washing hands, hygiene, don’t shake hands, cough into elbow - but compliance can be greatly improved. This is inexpensive. Still, it is unlikely to stop all future pandemics. It’s worth recommending more strongly. Sanitation has already given use huge gains here and can gives us further gains.

That leaves us with treating pandemics and vaccinating once pandemics start. This is a question of innovation.

Incentivising Innovation

The market arguably has inefficiencies with dealing with i) rare diseases and ii) developing world diseases and iii) diseases that have not occurred, but we can predict are likely to occur.

This is due to those markets being risky and/or commercially small and/or commercially small risk-adjusted (a market might be worth $2bn but at 1% chance of success, $20m risk-adjusted would be of small value).

Policy solutions that have (at least partially) worked have been a) granting longer/extra intellectual protection for rare diseases and b) agreed forward purchasing contracts for developing world diseases.

(a) Has helped areas such as rare genetic diseases, and multiple sclerosis (and other classified rare diseases) in the developed world (mostly) and

b) has helped in malaria and certain other developing world diseases (where commercial markets are smaller) - forward buying by the Gates Foundation amongst others.

Such mechanisms have mostly failed in I) developing new antibiotics against resistant strains, II) certain other developing world diseases, III) pandemics.

One negative factor in this is state appropriation of (mostly) private innovation. Rich countries eg US have been guilty of this as much as poor countries. The US essentially disregarded protection (or threatened to break the patents) on anthrax treatments in seeking to stockpile such medications cheaply. [https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1003966074330899280 ]

This causes a large disincentive to work on vital areas, if profit-seeking entities will lose out on their R&D development costs for such treatments.

I would propose (as others have done in various guises)

-partial speed up of regulatory response for areas of unmet medical need

-international “state capacity” in antiviral, antibiotic, mRNA, pandemic research

-forward purchase fund for pandemic vaccines and medications

Partial speed up of regulatory response for areas of unmet medical need

The gold standard in medical research are randomised controlled trials (RCTs). They are costly and slow, but typically generate the most robust results.

For low commercial value areas, RCTs (and previously trials needed before RCT) are too costly for entities to perform give the risk.

But, mostly health regulators will need RCTs before approval of a drug to be able to know the risk/benefit of a medication vs standard of care.

This has led some thinkers (eg Peter Thiel) to argue that regulators need to change or relax standards to allow quicker and more innovation on to the market. The challenge is that this may let onto the market ineffective treatments that cost lives or damage the credibility of the system.

One compromise would be to let medications on to the market where - in a controlled fashion - when there is enough evidence of safety/efficacy but no RCT. A full approval would be contingent on future RCTs being performed in a reasonable time frame else the drug would be with drawn from the market. The drug would also be withdrawn if the RCT fails.

If medications for areas of high unmet need - for instant pandemics or other diseases with limited treatment options - would be released this way, the net benefit would be positive.

Industry would pay for such a faster service, and this could cut drug development time in half.

International/national “state capacity”

Faster regulation alone would not help unless there were medications to test. Given the long and uncertain cycles for viral pandemics, it’s beyond the risk tolerance for many private entities. There are further complications because mutations might mean the plan A vaccine proves to be relatively ineffective and has to be made again under plan B.

However, I believe this is an area where even libertarians or perhaps “state capacity” libertarians might concede a non-private institution or set of institutions might be useful.

Essentially, I would be arguing for a form of Health ARPA where a part of the HARPA is focused on pandemic anteviral research, and antibiotic research and possibly other areas of unmet medical need. This is a sibling idea to the NIH but more targeted at likely pandemics.

If such an organisation had capacity to response quickly to evolving pandemics, then it should be able to share royalties with any other parties needed to scale medications to commercialisation, if it needed private partners to help scale quickly.

There should be positive spillover (cf NIH) in the years when no pandemics occur.

Forward purchase fund for pandemic vaccines and medications

Now (A) We have an organisation that can respond quickly with a new medication, and (B) a regulatory process which can speed through medications for high unmet need (eg pandemic) but how will we pay and keep incentives especially if we need multi-stakeholders to develop the medication.

This is where a forward purchasing fund or contract comes into play. This fund acts as a guarantee that a certain amount will be paid for the innovation in a swift manner. This is where CEPI already sits and comes in and the Gates Foundation (along with Mastercard and others) have made a sister CEPI for COVID specifically. I do note the US govt has approved funding quickly on COVID, but still better to have it already in place.

But, stronger and wider funding for CEPI (and I expect this will happen) would be a good development.

Conclusion

Given pandemics will re-occur, we should look to set up capacity to deal with pandemics, regulation that can be swift and responsive and a fund to guarantee a fair price for innovation and set incentives accordingly

Post Script: It turns out Bill Gates haas also written on this topic and he many similar ideas and sources (and talks more about infrastructure build) examples of certain pandemic preparation here. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2003762

Other Sources:

On some COVID maths https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2020/3/13/covid-brutal-maths-and-counter-factuals

On political age split: https://www.people-press.org/2016/09/13/2-party-affiliation-among-voters-1992-2016/

Moderna in trials: https://investors.modernatx.com/news-releases/news-release-details/moderna-ships-mrna-vaccine-against-novel-coronavirus-mrna-1273

On the CEPI funding call https://cepi.net/news_cepi/2-billion-required-to-develop-a-vaccine-against-the-covid-19-virus-2/

On Regeneron’s approach: https://newsroom.regeneron.com/static-files/2b0c3227-defd-4b84-814a-8519c89e103f

ON WHO list of treatment candidates:

Disclaimer and open letter:

Can you confirm the UK will be investing in COVID therapy research and will run trials this year, as according to the clinical trials database no trials are running?

Can you explain why, we should not significantly enhance UK treatment development protocols and potentially gain effective treatments or prophylactics this year, given certain biopharma companies are already testing treatments?

My thinking and letter on this is below.

Dear Patrick Vallance + UK team,

A safe vaccine or treatment with up to 40% chance of efficacy (maybe more) could be ready within 12 months. You’ve stated a vaccine is highly unlikely this year. This might be true under a traditional timeline, but if we invested under novel protocols we might significantly beat this.

(We met when you were at GSK and I know you have detailed knowledge of the traditional pathways, but I’m asking that you think about evoking an accelerated pathway).

Moderna has a vaccine in phase I safety trials (running as of March 2020). (There are others too.)

Regeneron has an antibody based programme that will have treatment available for trials in late summer.

If these trails show safety - there could be reasonable evaluation by May for the Moderna vaccine - then perhaps it is worth evaluating the risk of scaling up manufacturing and performing dosing in the elderly population? (Say, 20% - 40% chance of efficacy, this may be a good risk adjusted investment.) I think a £500m to £1bn investment could achieve this.

If this is not acceptable, then at least running an accelerated phase I/II/III trial here in the UK? I feel sure you would find the necessary volunteers.

This way, we may be able to accelerate a successful vaccine by up to 12 months from historic timelines. Or the antibody treatment could be available early 2021 or in 2020 under compassionate use. Is this not worth a chance?

We have evidence that several drugs might be effective treatments:

remdesivir (trials in China)

The anti-Il-6, Tocilizumab to treat cytokine release syndrome, a COVID-19 complication (China approved)

Chloroquine (China approved)

Baricitinib, Ruxolitinib (Rux is trialing in China already)

and many more.

Can you confirm the UK will be investing in this research and will run trials?

Now is the time to try fast and large scale innovation for a treatment and vaccine, and I feel sure that the UK could help lead the way here.

I wish you and your team every success.

Benjamin Yeoh

Notes and Sources:

Ben Yeoh is a healthcare investor with 18 years experience but is not a virologist or infectious disease expert. This is written in a personal capacity. This is an open letter to challenge traditional thinking based on biotech conversations that suggest accelerated timelines for treatments are possible. Ben believes government advisors should investigate this line of action. This is a personal view with no organisational endorsement. The view is made in good faith and should be investigated by those with expert knowledge. I suggest these ideas for public health reasons and there is no endorsement or not of any company mentioned for investment purposes.

On Moderna’s approach:

On Regeneron’s approach: https://newsroom.regeneron.com/static-files/2b0c3227-defd-4b84-814a-8519c89e103f

See slide 22.

Identification of baricitinib (and ruxolitinib) as treatments:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30304-4/fulltext

WHO database of drug treatments referencing ruxolitinib already in trials:

Details on Tocilizumab being approved in the 7th updated diagnosis and treatment plan for COVID-19 issued by China National Health Commission (NHC) on March 3, 2020 and the drug being in clinical trial.

Speculative ways of thinking about treatment + vaccine: https://www.thendobetter.com/investing/2020/3/14/covid-policy-vaccine-acceleration-proposal

Further details:

Vaccine probability of success

Vaccines have a 6% percent of success once in pre-clinical trials (base line stat) and around 16% when in phase I. Investors use a range of 1% to 16% chance of success typically for Phase I drugs. Risk is often bucketed for (a) safety (b) efficacy and c) regulatory.

There are plus/minus reasons to vary the risk of a COVID vaccine. Regulatory risk is lower than average. Reasonable people can argue for safety/efficacy risk. The mRNA technology is new, but we do have the virus genome. We know how to make flu vaccines very successfully, so it’s probably a matter of time and investment rather than completely new invention/innovation needed.

In any event, this is a >0 success rate, and a ball park 9% is reasonable for a novel phase I vaccine.

Vaccine and treatment idea details

Manufacturing in advance. This needs to start now as scale will be needed.

Trial for efficacy now. Ask for volunteer elderly, maybe healthcare worked and start the phase 2/3 test immediately in April/May. This is if you simply can’t push through vaccines when not yet tested.

If you scale up the money, you can run it on all 8 or so most viable vaccines, $8bn should be enough to take through an accelerated phase 2/3 + manufacturing if there is regulatory and company willing.

There are 80 or so drug treatment candidates identified by WHO. (see sources end)

We should start with drugs already approved and get them ready for trial in the field.

This would include chloroquine (already being used by China) and baricitinib (as identified by AI processes), China is running trials using ruxolitinib. These are treatments rather than preventative but still useful in curing patients and getting them out of ICU.

Costs

Moderna has already submitted a vaccine candidate using its mRNA technology. It’s currently being tested in safety trials. There are several other vaccine candidates, (cf. Inovio, Sanofi, J&J, GSK) but the speed is too slow - and it might not need to be this slow.

There is time and money needed to scale up manufacturing in case of success. This could be accelerated for $500m, if started now. That investment could be used to negotiate, say, a $15 price for the vaccine. USCDC pays $18 for a flu vaccine.

While the UK has only 12m elderly, maybe it could go halves with the US. Still an approx $1bn to $2bn investment per likely treatment candidate is viable and would potentially accelerate treatment into 2020.

Note, CEPI (Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations) has suggested $2bn for for up to 3 candidates to go forward finally past phase 3 (starting with 8 or so in phase I). So, about $1bn for one drug seems doable, at speed. Now the mostly traditional system, will have a good probability of success but it will be slow. So I’m suggesting a $1bn, 6% chance bet on one or 2 candidates now, for a chance for a vaccine in 6 months - that’s 12 to 18 months before the likely CEPI process. (We also know with some recent fast success in cancers. cf. Roche, Merck PD-1s, Novartis’ Gleevec some of this is possible at speed)

I’m also suggesting we allow drugs once they pass safety (or have passed safety), to be allowed into the field (this would cover Regeneron’s possible treatment, it would cover Chloroquine, baricitnib and ruxolitinib - these have already passed safety in other indications; it would be resmedivir as well)

Also, note there might be antibody treatments - this would be Regeneron’s approach. It won’t have antibodies ready until summer, but once ready, after a short safety trial, it might be worth going to dose the elderly. So say doses ready in August, safety trial Sep - get it ready now - and start dosing in October. This could be expensive but only in the order of $2bn to $8bn depending on price. Now, in October we won’t know efficacy, but if safety is basically clear, then again we have a 20 - 40% chance of success albeit at a higher cost (as antibodies are more expensive).