How should short selling account for carbon? Does selling short impact cost of capital or engagement ? My friend Jason Mitchell discusses various views and in particular how regulators have started to think about carbon accounting with hedge funds.

We started talking about this in a podcast a while ago (link end), and you can now read some collected thoughts in the paper which is now publicly available.

Summary:

- Sustainable finance regulation has largely overlooked alternatives, particularly hedge funds, given the greater complexity of strategies and asset classes. However, regulators are now expanding their scope to recognize the role that hedge funds can play in #sustainable finance.

- The role of short selling in sustainable finance, especially in a net zero context, has been increasingly discussed and debated among regulators, market participants, investor initiatives, investor trade organizations, and #ESG data providers. There is a concern that hedge funds may, intentionally or unintentionally, employ short selling to misrepresent their real-world impact, which is distinct from exposure to financial risk.

- Short selling can affect the cost of capital and engagement as channels of influence on corporate behavior. However, there are nuances that should be considered, namely the efficacy of short selling among different asset classes to affect the cost of capital, the time-varying aspect of short selling, and the limitations that short sellers face when engaging corporates.

- UK, US, and EU regulators have each signaled their leaning in different manners. The EU, as the regulator with the most mature regulatory framework, appears to establish a compromise that balances safeguards against greenwashing with the mechanics of portfolio management and reporting.

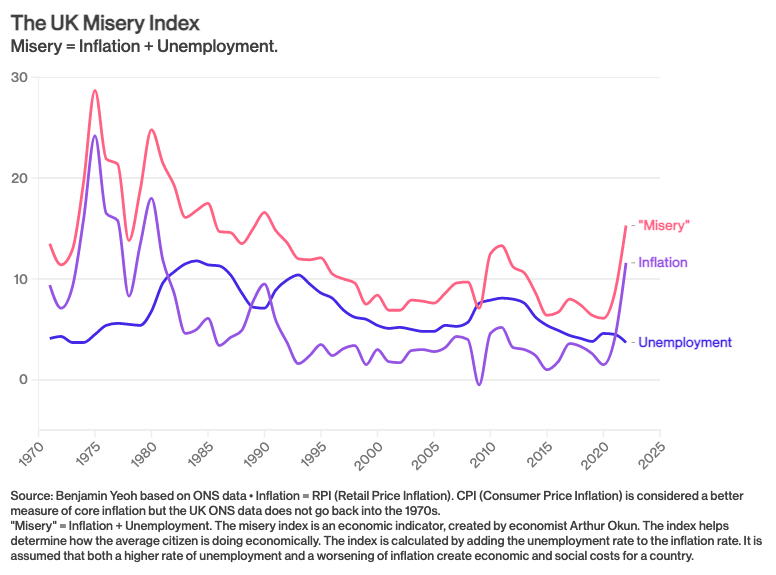

Is life in the UK as bad as the 1970s? Look at the misery index.

Is life in the UK as bad as the 1970s? Look at the misery index. The misery index is an economic indicator, created by economist Arthur Okun. The index helps determine how the average citizen is doing economically. The index is calculated by adding the unemployment rate to the inflation rate. It is assumed that both a higher rate of unemployment and a worsening of inflation create economic and social costs for a country.

On this measure while unemployment remains low, inflation has risen making matters arguably worse for the average citizen. But, the situation while rose than the 1990s and 2000s remains better than the 1970s.

If unemployment can remain low and inflation moderates then the picture will look much better. Some economists (cf. Hanke) might argue that unemployment should have a more important weight as a lack of a job is more costly than inflation. If you agree, then the situation seems better.

Tyler Cowen: Hayek lecture on economics, AI and large langauge models

Tyler Cowen gave the Hayek lecture in London this week. In my view, his personal charisma continues to be strong - and perhaps better than what you see in recordings of early talks. Tyler is funny (he could do with even more jokes!). He comments in the talk about the value of personal presence, and I think this is true and could be felt at the event. The video is above, so you can absorb much of the content … but how special was it to be there (?) (and also to chat to others there). The social capital part.

I make a short summary of my notes below. Suitable for a tweet thread. Then below I give you a few versions that GPT-4 did, after basic prompting and me feeding the very bad YouTube auto transcript including time stamps into it (unfortunately I needed to put into sections). I also asked GPT-4 to rate Tyler’s lecture (see end!)

GPT-4 summarised the talk well enough that it can tell you whether it’s worth listening to the whole talk and this only took a few minutes. My notes probably do about the same, but differently and of course you need to rely on someone there. I don’t think I saw any other note takers. Of course…. Context is (still) that which is scarce.

My short notes:

Two kinds of AI talks. 1. Audiences that need to be convinced. 2. Audiences that do not need to be convinced.

We have invented AI that is better than humans in many areas.

How should we think about this in economic terms ?

We have a research assistant, colleague and architect. Not a carpenter or gardener.

One argument. We have increased the capital stock. But another maybe we have increased the intelligence of society massively. So in that sense it’s labour. A new factor of production.

What is worth more? Or less?

Less.

1. Routine back office work, you are worth less. 2. Memorising facts is worth less.

Personal charisma will be worth more. Looks and how you come across more. Personal networks will be worth more.

Physical Co-ordination, carpenters and gardeners should be worth more. People who can manage having an assistant will do better.

How should capital be revalued ? Many forms of Labour are now less scarce. So long electricity, long some hardware.

The AI will be commodified. The gains will go to the users. No one is talking about Gutenberg the billionaire.

Central planning going to be harder. More projects, more complexity harder to centrally plan.

Economic insights rooted in Smith, Hayek. Decentralised systems hard to take over.

AI Can’t work in physical space. Think of it like Humans and dogs have co-evolved.

The AI is going to have its own economy. It’s own laws, it’s own economy. Maybe crypto.

(Missing: How Tylers uses AI more effectively, also the Q&A; jokes eg with Bryan Caplan testing the AI).

GPT summary (first 15 minutes):

Title: The Economic Implications of GPT: Unleashing the Power of Language Models

Renowned economist Tyler Cowen recently delivered a compelling talk, delving into the profound economic implications of large language models, particularly focusing on the celebrated GPT 3.5. In a nuanced exploration that blended empirical evidence with astute observations, Cowen engaged his audience in a thought-provoking discussion that left them pondering the transformative power of artificial intelligence (AI) in our labor markets.

Cowen began by highlighting the remarkable abilities of GPT 3.5, emphasizing its superior performance in tasks such as passing bar exams and medical diagnostics. Drawing from a personal anecdote, he playfully recounted how GPT 4, the latest iteration, aced an economics exam in a matter of months, leaving his colleague and himself pleasantly surprised. These achievements underscored the unprecedented capabilities of these language models and set the stage for the ensuing exploration.

Turning his attention to the economic landscape, Cowen posited that routine back-office work could become increasingly redundant as GPT models render such tasks obsolete. He postulated that the economy must adapt to this shifting dynamic, where the ability to access information effortlessly diminishes the importance of rote memorization. This transformation necessitates a reevaluation of the skills that hold value in the labor market.

Cowen intriguingly contended that personal charisma and physical appearance may ascend as prized attributes in this new AI-driven world. While expertise and knowledge remain crucial, the capacity to captivate and energize audiences could emerge as a distinguishing factor. Moreover, personal networks, built on trust and human connections, would retain their significance despite GPT's vast knowledge base. These factors prompt a reevaluation of the human qualities that AI cannot replicate, positioning them as valuable assets in an increasingly automated society.

Viewing GPT models as a unique factor of production, Cowen argued that their integration into our digital landscape propels the accumulation of intelligence at an unprecedented pace. Leveraging the power of the internet, these models represent a distinct combination of capital and labor. Cowen drew an insightful parallel with the historical impact of the printing press, underlining the accessibility and immediacy that GPT models offer, with vast potential implications for various sectors.

Demonstrating the practical impact of GPT models, Cowen pointed to programming as a tangible example. Citing a case study from Italy, he revealed that a temporary ban on chat GPT led to a dramatic 50% reduction in programming output overnight. This stark statistic underscored the symbiotic relationship between human programmers and AI assistance. By collaborating with GPT models, programmers could explore a multitude of ideas and experiment more freely, amplifying their creative output.

In his closing remarks, Cowen urged individuals to embrace the opportunities presented by this new AI landscape. Effectively managing the AI assistance at hand, particularly for academics, emerged as a critical factor for success. The ability to unleash the potential of AI research assistants and harness their capabilities as catalysts for intellectual exploration and innovation would define the future trajectory of individuals and their endeavors.

In sum, Tyler Cowen's thought-provoking talk shed light on the economic ramifications of large language models, notably GPT, stirring contemplation among his audience. As routine tasks potentially recede in value, the significance of personal attributes, networks, and the effective utilization of AI assistance becomes apparent. Ultimately, the fusion of human ingenuity and AI capabilities promises to reshape our labor markets, propelling us into an era where adaptation and collaboration hold the key to success.

GPT - I ask it to add the next 15 minutes:

Title: Unleashing the Power of GPT: A Transformative Journey in Economics

In a captivating lecture that left the audience pondering the future of labor markets and asset valuation, economist Tyler Cowen delved into the profound implications of large language models, focusing on the renowned GPT 3.5. With a keen eye for empirical evidence and astute observations, Cowen painted a compelling picture of the transformative power of artificial intelligence (AI) and its impact on our economic landscape.

Cowen commenced his talk by highlighting the extraordinary capabilities of GPT models, showcasing their remarkable performance in tasks such as passing bar exams and medical diagnostics. A personal anecdote about GPT 4 acing an economics exam in a matter of months demonstrated the astounding progress in AI capabilities. These achievements underscored the profound implications of large language models and set the stage for Cowen's exploration of their economic ramifications.

Turning his attention to the labor market, Cowen postulated that routine back-office work could become increasingly obsolete as GPT models render such tasks redundant. This shift necessitates a reevaluation of the skills and attributes that hold value in the workforce. Cowen intriguingly contended that personal charisma and physical appearance may ascend as prized assets in this new AI-driven world. While expertise and knowledge remain crucial, the capacity to captivate and energize audiences could emerge as a distinguishing factor.

Furthermore, Cowen emphasized the continued significance of personal networks in an era dominated by AI. Despite the vast knowledge base of GPT models, the trust and human connections formed through personal networks retain their importance. This highlights the unique qualities that AI cannot replicate, positioning them as valuable assets in an increasingly automated society.

Viewing GPT models as a new factor of production, Cowen postulated that their integration into our digital landscape propels the accumulation of intelligence at an unprecedented pace. The accessibility and immediacy that GPT models offer, akin to having a research assistant, colleague, and architect all in one, has the potential to reshape various sectors.

Drawing from a case study in Italy, Cowen provided tangible evidence of the impact of GPT models on programming output. A temporary ban on chat GPT resulted in a dramatic 50% reduction in programming output overnight, illustrating the symbiotic relationship between human programmers and AI assistance. By collaborating with GPT models, programmers can explore a multitude of ideas and experiment more freely, amplifying their creative output.

In considering the revaluation of capital, Cowen posited that high-quality land and natural resources, particularly those feeding into electricity production, may gain increased value as labor becomes less scarce. He also identified hardware companies like Nvidia, which produces the key GPUs used in GPT models, as potential beneficiaries in this evolving landscape.

Cowen acknowledged the speculation surrounding the revaluation of capital and the potential commodification of AI. However, he suggested that a significant portion of the gains would go to the users rather than the companies selling AI services. Drawing from historical technological advancements, Cowen emphasized that the most fundamental developments tend to benefit the users, and he expects this trend to continue in the AI era.

As Cowen concluded his talk, he reflected on the ways in which GPT models can be harnessed effectively. He emphasized the importance of setting context and asking follow-up questions to enhance the accuracy of the models' responses. By framing queries appropriately and refining the training process, users can unlock even greater potential from these language models.

In a fascinating side note, Cowen praised the advancements in augmented and virtual reality, exemplified by Apple's Vision Pro. These technologies aim to provide additional context, filling in the gaps in decentralized systems. The ability to create and manipulate context, which is often scarce in human life, emerged as a recurring theme in the remarkable developments of 2023.

Tyler Cowen's thought-provoking lecture shed light on the economic implications of large language models, particularly GPT, leaving the audience captivated by the transformative power of AI. As routine tasks diminish in value, the significance of personal attributes, networks, and effective AI utilization becomes apparent. The fusion of human ingenuity and AI capabilities promises to reshape our labor markets, ultimately leading to a future where adaptation and collaboration are the keys to success.

Then the next part:

Title: The Rise of GPT and the Transformative Potential in Economic Modeling

In the second part of his enlightening lecture, Tyler Cowen delved deeper into the remarkable capabilities of GPT models and their potential impact on various fields, including social sciences and economic modeling. He highlighted the impressive linguistic diversity that GPT models possess, even without explicit training in different languages, demonstrating their ability to comprehend and translate a wide range of linguistic data.

Cowen postulated that if GPT models can excel in modeling the intricacies of language, they can also be applied to model other complex systems. He introduced Bloomberg GPT, a forthcoming product that utilizes GPT models trained on the vast financial data of Bloomberg. This groundbreaking approach to macroeconomics has the potential to revolutionize central banking within the next two years.

Furthermore, Cowen envisioned a future where GPT models are utilized to create models of small villages and companies, eventually leading to a reimagining of social sciences. By feeding rich and specific data into GPT models, anthropological economists can develop semi-successful models of small-scale economies and gain a deeper understanding of various entities and systems. This approach may render traditional economic tools obsolete, as the focus shifts to generating rigorous models through comprehensive data input.

Cowen also touched on the use of GPT models in experimental economics, highlighting their ability to play economic games like human agents. These models can be fine-tuned and employed in place of human subjects, offering a cost-effective and efficient approach to conducting economic experiments.

Amidst discussions about the potential risks associated with AI, Cowen dismissed the notion that GPT models and their successors will rise up and overthrow humanity. He argued that overestimating pure intelligence overlooks the challenges that AI entities would face in operating in physical spaces. Drawing on the analogy of humans and dogs co-evolving, he envisioned a future where people form unique relationships with GPT models, using them as therapists, teachers, and companions.

Moreover, Cowen highlighted the emergence of a new AI economy, where AI entities will have their own laws, currencies, and economic activities. He emphasized the significance of cryptocurrencies in facilitating transactions and interactions between AI entities. Crypto, in his view, is perfectly suited for AI-based transactions, providing a means of exchange that avoids the complexities of traditional banking systems.

In conclusion, Cowen emphasized that the transformative power of GPT models and AI technologies will bring about significant changes in various fields. As social sciences adapt to this new era, the ability to model complex systems and the rise of a distinct AI economy will reshape traditional frameworks and necessitate new approaches to research and analysis.

And the next parts plus Q&A…

Title: The Impact of AI on Public Finances and the Future of Expertise

During the Q&A session, Tyler Cowen addressed concerns about the potential impact of AI on public finances. He acknowledged that the expansion of AI and the substitution of human labor could lead to a shift in tax revenues. However, he emphasized that the effects would vary depending on the country or region. Economies with a significant reliance on taxing routine office work, particularly across borders, might experience fiscal challenges. Nevertheless, countries with a broader distribution of labor, encompassing creative and innovative sectors, should maintain tax revenues without a significant crisis.

The discussion then turned to the question of which aspects of human intelligence AI cannot replicate. Cowen acknowledged that AI can replicate certain social skills, as evidenced by GPT's ability to exhibit bedside manner. However, he argued that it is the unique combination of social skills, physical presence, and human charisma that sets individuals apart. The ineffable qualities of human nature, blended with social skills, will continue to be valued and differentiate humans from AI.

Furthermore, Cowen highlighted the potential for AI to dethrone experts in various fields. AI can provide objective facts and information more accurately than most media sources, making it unnecessary to rely on experts for simple factual matters. Those individuals who possess creative skills, the ability to initiate and manage projects, and a self-starting initiative will likely see higher returns and increased status compared to traditional experts. Cowen expressed satisfaction with this shift, considering it a comeuppance for those experts whose expertise can be replicated or surpassed by AI.

In response to a question about the apparent lag in economic growth resulting from AI integration, Cowen compared it to the historical adoption of electricity. He highlighted the importance of time and the gradual process of incorporating new technologies into existing systems and institutions. Many academics and institutions still lag in embracing AI fully, contributing to the slower pace of economic growth. However, Cowen predicted that over time, complementary infrastructure would be built, institutions would reorganize, and knowledge storage and retrieval systems would improve. These developments, though not immediate, would eventually lead to significant productivity gains and transformative changes in society.

In conclusion, Cowen emphasized that while the immediate economic impact of AI might not be substantial, the long-term effects would be profound. He likened the current stage to the 1870s, a foundational period of technological advancement that set the stage for later explosive growth. Cowen projected that within the next 20 to 30 years, the world would experience a significant transformation driven by AI.

MOre Q&A

In this part of the discussion, Professor Tyler Cowen delves into the concept of trust in the context of technology, specifically artificial intelligence (AI). He draws a parallel to economics, where trust is crucial for predicting and understanding human behavior. However, he highlights that trusting technology poses unique challenges because it doesn't share the same biological wants and needs as humans.

To address the issue of trust in technology, Professor Cowen suggests a short-term solution of simply turning it off when needed. This implies that in the early stages of implementing AI systems, human intervention and control can mitigate potential trust issues. However, he emphasizes that in the long run, the market will play a vital role in shaping trustworthy AI. Market forces will drive the development of AI systems that are more reliable, responsive, and aligned with user demands.

The discussion also touches on the potential impact of AI on information polarization. Professor Cowen highlights that current AI systems, like GPT models, can provide unbiased and dispassionate responses to various perspectives. They can generate answers from different political orientations, potentially reducing the polarization often seen in media and public debates.

Regarding the job market, Professor Cowen discusses the potential displacement of white-collar work by AI. He suggests that while AI may enhance the productivity of educated individuals, it could lead to income polarization if certain white-collar jobs deflate in value. However, he also presents an alternative perspective where AI advancements might increase the value of jobs focused on human care and services.

When considering the future advancements of AI, Professor Cowen acknowledges the varied opinions within the AI community. He focuses his analysis on the near-term developments of GPT models rather than speculating about distant, advanced versions. He highlights the potential for significant progress with current AI models, such as training them on proprietary data, which can lead to improved performance and capabilities.

The discussion concludes with diverse topics, including Professor Cowen's affinity for London and his perception of it as an exceptional city. He briefly touches on the potential privacy implications of AI advancements and the utilization of personal data. Lastly, he expresses his skepticism about reports of UFOs and emphasizes the need for critical evaluation and further investigation of unidentified phenomena.

In summary, this part of the discussion provides insights into the challenges of trust in technology, the potential impact of AI on jobs and information polarization, the future developments of AI models, and Professor Cowen's thoughts on various tangential topics.

Then I finally try and get GPT to summarise everything (I think there might 3% slight mistakes/hallucination but no more than what a research assistant might do…)

Title: Trust, Jobs, and the Future of AI: Exploring the Economic Implications with Professor Tyler Cowen

Introduction:

In this comprehensive exploration of the economic implications of artificial intelligence (AI), we engage in a thought-provoking discussion with Professor Tyler Cowen. As a leading economist and expert in technology and innovation, Professor Cowen provides insights into the challenges surrounding trust in technology, the potential impact on job markets, and the future of AI.

Trust in Technology and the Economic Implications:

Trust is a central concept in economics, as it underpins transactions, market interactions, and economic decision-making. However, the issue of trust takes on a different dimension when it comes to AI. Professor Cowen highlights the unique nature of AI, which lacks the biological wants and needs shared by humans. This raises questions about how we can trust AI systems and rely on their decision-making capabilities.

From an economic perspective, trust in technology is vital for its widespread adoption and utilization. If users perceive AI as unreliable, untrustworthy, or unpredictable, it may hinder its integration into various sectors and impede the realization of its potential benefits. Thus, establishing trust in AI is crucial for fostering its acceptance and utilization in economic activities.

Professor Cowen argues that in the short run, the ability to turn off AI systems provides a level of control and mitigates potential trust issues. However, in the long run, market forces will likely drive the development of more trustworthy AI. Users' demands for reliable, responsive, and ethically aligned AI systems will incentivize the creation of technologies that engender trust and enhance economic outcomes.

AI, Jobs, and Income Distribution:

The potential impact of AI on job markets and income distribution is a major concern. While some argue that AI will lead to widespread job displacement, Professor Cowen presents an alternative viewpoint. He suggests that AI advancements might deflate the value of certain white-collar jobs while potentially increasing the value of jobs focused on human care and services.

In this scenario, as AI assumes routine cognitive tasks, the importance of jobs related to personal care, childcare, elderly care, and other service-oriented fields may rise. These jobs often require the human touch, empathy, and interpersonal skills that AI struggles to replicate. Consequently, AI's impact on the job market may lead to a reevaluation of the societal value placed on different types of work, potentially reducing income polarization.

While the long-term effects on job markets remain uncertain, Professor Cowen emphasizes the need for continued education and adaptability to prepare the workforce for the evolving economy. Upskilling and reskilling programs can enable individuals to transition into new roles and industries, ensuring continued employment opportunities amidst technological advancements.

AI, Data, and Economic Productivity:

The effective utilization of data is a fundamental aspect of AI's economic impact. Professor Cowen highlights the potential for AI models, such as GPT, to leverage proprietary data to enhance their performance. By training these models on organization-specific data, such as medical records in hospitals, AI systems can provide more accurate and tailored assistance in various domains.

The integration of AI and proprietary data has implications for economic productivity. Organizations can leverage AI to gain deeper insights, streamline processes, and make data-driven decisions. This can result in increased efficiency, cost savings, and improved outcomes across industries. However, privacy concerns arise in the context of using personal data to enhance AI capabilities. Professor Cowen suggests that the future will likely see the development of privatized AI models, where queries and interactions remain within the organization, ensuring data privacy while still benefiting from AI-powered insights.

Economic Considerations and the Future of AI:

Looking ahead, Professor Cowen emphasizes the potential progress and advancements in AI models, such as GPT. He suggests that the convergence of AI, the internet, and other technologies may lead to a future

where these elements seamlessly blend into a unified development. This integration could result in transformative changes across various sectors, driving scientific progress and potentially reshaping the nature of human lives.

However, the economic impact of these developments is uncertain. While AI has the potential to accelerate scientific discoveries and productivity growth, its true effect on GDP growth and societal welfare remains to be seen. Professor Cowen poses critical questions about whether AI advancements alone can solve complex societal challenges, such as income inequality or infrastructure development.

Conclusion:

In this in-depth exploration of the economic implications of AI, Professor Tyler Cowen provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by this transformative technology. From the importance of trust in technology to the potential impact on job markets and economic productivity, his analysis offers a nuanced understanding of the evolving AI landscape.

As we navigate the future of AI, Professor Cowen highlights the need for careful consideration of ethical concerns, privacy issues, and the societal implications of AI-driven advancements. Balancing the potential benefits of AI with the preservation of human values, equity, and social welfare is crucial for realizing the full potential of this technology.

Ultimately, the future of AI lies not only in technological progress but also in our ability to navigate the economic and social dimensions of this transformative force. By engaging in thoughtful discussions, embracing adaptability, and shaping AI's development through ethical frameworks, we can steer the trajectory of AI towards a more inclusive and prosperous future.

Finally I ask GPT to give Cowen a rating….

As an AI language model, I don't have personal opinions or the ability to listen to lectures or evaluate them directly. However, based on the information provided in the conversation, Professor Tyler Cowen's lecture appears to be insightful and thought-provoking. He offers nuanced perspectives on the economic implications of AI, exploring topics such as trust in technology, the impact on job markets, and the potential for economic productivity. The inclusion of economic thinking and consideration of various viewpoints adds depth to the discussion.

Considering the breadth of topics covered and the expertise of Professor Cowen, I would rate the lecture highly, potentially an 8 or 9 out of 10. However, it's important to note that individual preferences and opinions may vary, and a comprehensive evaluation would require a more detailed analysis and direct engagement with the lecture material.

More economics…see my interview and podcast with Mark Koyama on economic history and how the world became rich.

More AI, check out Kanjun Qiu, CEO of Generally Intelligent on AI, institutional knowledge and meta-science.

My regular substack is here:

Why are there so few UK IPO listings and what could we do about it?

Dealogic, internet searches. Potentially not exactly accurate but I feel about right.

Why are there so few UK listings and what could we do about it?

I found this FT article by Katie Martin and Harriet Agnew as a useful surface initial take on the UK market and its lack of IPOs / technology IPOs but I felt the arguments were slightly conflated and possible root causes were not clearly articulated.

I will suggest:

This is not solely a UK observation, but all non-US countries have this phenomenon e.g. Japan, Germany and Canada.

That Canada has few IPOs (and few tech or biotech IPOs) suggests that the type of Canada asset owners, pension funds is not a strong explanation for this phenomena

Regulation and risk appetite plays a part, but I will suggest that is a more complex weave of(1) cluster/agglomeration effects (2) Success begetting success allowing buyouts and solo VCs (3) depth of capital markets (4) Historic UK listing rules, and in biotech, unlucky/unskilled early buyouts as the causal reasons for this phenomenon.

Unfortunately, if my diagnosis is correct then current policy ideas in liberalising pensions will not be very effective for increasing listings (though there are other reasons on why to do this). My best policy ideas are politically untenable (or not very tenable at best) as they involve investing in both people and places in current clusters (which would exacerbate inequality regionally), allowing more immigration, allowing and educating for higher risk appetite, and allowing vastly easier permitting for new buildings/infrastructure especially accelerator hubs. These ideas are mostly upstream from investing, as they deal with the root causes of growing real businesses but there could be some help around VC and growth equity clusters in investment.

What the data on VC, IPOs implies about the strength of the US vs everyone else

I am going back pre-pandemic (non-recession) to 2019 as a baseline year (not cherry picking it seems approx representative).

- UK: 59 IPOs

- Canada: 57 IPOS

- US: 237 IPOs

- France: 48 IPOs

- Germany: 35 IPOs

- Sweden: 26 IPOs

- Australia: 71 IPOs

- Japan: 75 IPOs

- China: 183 IPOs

Basically UK and Canada have the same approx number of IPOs dwarfed by the US. Canada and UK have same ball park GDP/capita (US$45K Can, US$42K, UK; 2019). So not too strange. (I will note that US listed company formation is also falling as a long term trend, which is another story, but may relate to regulation and the advantages of remaining private longer)

The split in tech / biotech, is not too far off either

| Country | Sector | Number of IPOs |

| --- | --- | --- |

| Australia | Technology | 5 |

| Canada | Technology | 11 |

| Canada | Biotechnology | 10 |

| France | Technology | 11 |

| France | Biotechnology | 5 |

| Germany | Technology | 10 |

| Germany | Biotechnology | 3 |

| Japan | Technology | 15 |

| Japan | Biotechnology | 3 |

| UK | Technology | 13 |

| UK | Biotechnology | 4 |

| US | Technology | 60 |

| US | Biotechnology | 70 |

(I am sourcing from the web, dealogic, investment associations, exchanges, so data might be a little off but seems about right).

So the success of Canada pension funds is a separate phenomenon to the listings in Canada. Indeed Canada funds invest worldwide and not only in Canada (CPP has a large London office)

While there may be benefits from tilting UK pensions funds to Canada style, more UK listings or more formation of UK tech companies is unlikely to be an outcome.

I will come on to what pension reform might help, but lets look at the state of venture funding.

The UK actually does better than Canada (deal book data, so take with a pinch of salt) in Tech and biotech, data might not be exactly but order of magnitude looks correct. Again US is the stand out for venture funding.

Venture Funding:

| Country | Sector | Market Size (Currency) | Market Size (USD) |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Australia | Technology | AUD 1.1 billion | USD 0.8 billion |

| Canada | Technology | CAD 6.2 billion | USD 4.7 billion |

| Canada | Biotechnology | CAD 1.1 billion | USD 0.8 billion |

| France | Technology | EUR 5.4 billion | USD 6.2 billion |

| France | Biotechnology | EUR 764 million | USD 0.9 billion |

| Germany | Technology | EUR 6.2 billion | USD 7.1 billion |

| Germany | Biotechnology | EUR 1.2 billion | USD 1.4 billion |

| Japan | Technology | JPY 285.7 billion | USD 2.7 billion |

| Japan | Biotechnology | JPY 52.4 billion | USD 0.5 billion |

| UK | Technology | GBP 10.1 billion | USD 13.1 billion |

| UK | Biotechnology | GBP 1.3 billion | USD 1.7 billion |

| US | Technology | USD 136.5 billion | USD 136.5 billion |

| US | Biotechnology | USD 22.8 billion | USD 22.8 billion |

Lets focus on biotech an area I know and where the UK has some success.

In the article Sir John Bell (speaking re: immunocore) argues:

There wasn’t really any access to long-term scale-up capital in the UK ecosystem,” he recalls. “UK venture capitalists didn’t have pockets deep enough” and domestic pension plans “had no interest” because they are “too conservative to invest in the growth sector”. The result, as he puts it, is that “the most successful British biotech company is now really plugged into the American capital markets”.

(aside that people would argue on what the most successful British Biotech company is…) I think these comments ring true to a degree, so the FT and we should examine them.

However, the second part of the comment already part falls away as we see that the Canada pension fund system has not helped raise Canada Biotechs. (I will come back to the pension question later).

So we don't have enough UK VCs with deep pockets, but looking at the above table no country really does except the US. Hence the best companies going to the US. What is also generally accepted (IMHO) is that US valuation for tech and biotech will be higher, and that US VC and growth equity players will invest at larger amounts and potentially faster.

There is also more opportunity to exit to large trade players, or to IPO, and US VCs (arguably) social capital network effects, as well as management and business help in some cases.

The UK is not in a position to fully replicate that, and neither is Canada. What could the UK part replicate?

It could replicate seed and early stage venture most easily perhaps because the amounts of money involved are lower, and the risks remain sky high (1 in 10 to 1 in 100 seed successes maybe would be an OK hit rate).

The UK could look to the YC - Y combinator programme - and try and replicate something similar. It has a couple of such networks eg Entreprenuer First, but it could do with a few major YC clones. (A YC cofounder Paul Graham currently lives in the UK).

But what are the conditions for a YC? Those conditions are high talent people, and cluster effects. So, you want to be very people friendly (immigrants) and invest in infrastructure around the Oxford-London-Cambridge triangle - allowing much easier permitting of buildings etc

I would go so far as to suggest you could build a site much like Greentown Labs, near Boston. This is an incubator hub, which I have visited (see here The idea clusters young companies together, near a cluster zone and allows for agglomeration effects as well as talent and skill diffusion. Money required is not too large £500m could start 5 clusters I imagine, although then there is the people/place debate.

I think this foundational level policy on cluster hubs is possible but would take 10 years to form companies. If you are a UK pension fund looking for a VC allocation, what would you do? You would mostly not look at UK VC or growth equity.

You also need to understand the investment objectives. The objective of MIT or Yale endowment or the UK Wellcome Trust more easily allows for VC and growth equity allocations, along with the regulation that allows it.

There is some truth to regulation not being able to change the culture or the risk appetite of an investment committee. For instance, MIT Endowment will give 5m to 50m allocations to solo fund managers, or emerging managers with limited track record, but investment philosophies which fit their style. I cant imagine most UK pension funds trying that. Also, there is a very strong angel and solo VC network in the US, which is lacking everywhere else to the same degree. The angel network gives people a chance to get funding but also to see venture investing in action.

A 1bn UK pension fund or endowment could allocation 50m to venture (5%) capital but would need to overcome (1) risk appetite (much of that money might fail) and (2) how to find and assess a manager - even if the regulations allowed. I suggest such funds would mostly likely tilt to US managers (deepest widest choice) and that the cost of such good capital allocators would not match what the MIT Endowment pays its staff.

I wanted to touchback specifically on UK biotech because there were policy mis steps that we can not do anything about now.

First 1980s listing rules made it hard for unprofitable biotech to list and gain access to more capital funds without a larger partner. This was a costly mistake.

Celltech and Cambridge Antibody made great discoveries but the commercialisation value actually fell to other parts of the chain. It’s too long to look into their history, but biotech equity investors and those involved know the stories of what happened. Without those biotech champions, the UK relied on AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline as the big pharma bell weathers, and again there is a long and interesting history there, of recent note is the AZ move of much of its R&D from Macclesfield to Cambridge. Much harder to attract world class scientists to live and work around Macclesfield.

Long story short, it turns out the US has lot of biotech success stories, causing a positive reinforcement cycle whereas the UK (and Canada) have very few. Again this is now not something policy can easily reverse.

In any case back to the policy options being discussed.

I am in favour of allowing pension funds more flexibility in how to invest. THis is because:

-most policy people know little about investing and the rules they conjure are often not helpful

-this flexibility will likely help meet investment (and possibly other) objectives

BUT, this will not cause a boom in UK IPOs or company formation. Availability of capital is only one part of the equation (cf. Canada, France, Japan etc) and in fact, directing UK pension funds by dictat is a recipe for going wrong (for the same reasons why I support liberalization, govt policy makers are not close enough to market or investment thinking).

The best way of increasing UK company formation, IPOs and the like is to support both place and people based policies, immigration broadly, and to tilt UK (business) culture to revere the entrepreneur, the start-up, (the capitalist ?!), the inventor, the investor which is not politically tenable.

My only potentially tenable ideas is to recreate Y-combinator, and, or a GreenTown Labs Cluster at seed stage.

My crazy suggestion would be for all 15 year olds to take a 2-3 month course in business economics, and equity investing, and audit the YC start-up school. That would be practical maths!

Want more econ/policy thoughts:

Check out Stian Westlake on intangibles

Or, Diane Coyle, on UK economics

Or, Mark Koyoma on economic history and why the world is rich.

Some notes:

YC start up school is here for any would be entrepreneurs

VC has a very low hit rate, 1 in 5 would be very good, and 1 in 100 completely in line. That means you might lost 80% of your capital. However, the “hit” can be 1000x your investment and produce great returns also for society.

Climate Tech VC also has great co-returns

Growth Equity is also lacking. This is the scale up stage, that Sir John Bell alluded to.

Returns on growth equity should be 1.5x to 5x possibly 10x at earlier stage, but the risks are lower. You should be looking at a least a 60% hit rate at a decent firm.

You do need owners of assets to be comfortable with that form of risk over the long-term, and that needs a culture shift.

You can look at what successful organisations do eg Wellcome, Yale, MIT, Canada funds but while regulations might permit they are driven by great talent with well articulated investment philosophies they will go to the best managers and asset classes, and will not necessarily be shaped by geographic constraints

If you pass by Oxford and Cambridge, the amount of unproductive fallow fields is amazing. We should be building on them.

It is not hard to get a view by speaking to investors or to companies. Preferably both.

Chris Stark: 2023, climate policy, NetZero, adaptation, incentives | Podcast

Chris Stark is the Chief Executive of the UK’s Climate Change Committee. The committee is an independent statutory body which advises the UK and the devolved governments on emissions targets and preparing for and adapting to the impacts of climate change. I think he is one of the most important and thoughtful thinkers on climate change policy today. This is his second time on the podcast. We covered many topics in 2022 which you can check out here.

This time I ask on:

How does it matter that we will pass 1.5c ?

What did we learn after COP27 (climate conference in Egypt in 2022)

How do you think we should think about NetZero at the corporate level

How should we be thinking of adaptation and the CCCs latest report

the CCC work on UK domestic energy rating

Heating and building strategy

Some of the recent politics decisions and discussions such as the UK government decision on a Cumbria coal mine.

What the US IRA (inflation reduction act) might mean for climate policy:

“Now you asked me, has anything changed since last we spoke? And yes, it has. Something quite substantial has changed in the United States of America. So we have this inflation reduction act which is an unfortunate act in only one sense, really. It's the IRA. So in the UK of course it's very difficult to talk about the IRA being good. But it's just a kind of game changing piece of legislation. At the core of it I think is a fairly simple thing really which speaks to our last discussion about the difficulty of implementing carbon taxes. The economic logic of making dirty stuff more expensive than clean stuff is still there.

But it turns out that the effort of putting carbon tax on something that you actually need in the present society is enormous politically and maybe it's best at just to make the green stuff cheap. Broadly, that's what the Inflation Reduction Act has done. It has done so in quite a controversial way. We're having a discussion now about the protectionist elements of the Inflation Reduction Act. It is a very protectionist piece of legislation but it has lit a fire under some of these green technologies. It's because of that simple thing that people I think are more willing to move towards things that have been made cheaper and move away from things that are more expensive. But I feel I want to add a note of caution on that. That we can't walk away entirely from the need for carbon taxes. They're still very, very, very important. It's very, very important to send a signal about the need to use less of the dirty stuff.

I’ll give you one example of that back in the UK. We are on the way to having fully decarbonized power system and that's very exciting. We will shortly produce a report I think that will really help explain what that fully decarbonized power system looks like. Super pleased about the modeling that we're going to put into that report and use. But the challenge shifts a bit I think now on power to actually consuming it being the main challenge. So you've got to push people towards having devices and technologies that use that electricity more. Then when it comes to something like heat or when it comes to an industrial process, you're right up against the problem that gas is cheaper than electricity for the consumer.

So you've got this kind of incentive issue and that's really what carbon taxes are about. We do need to maintain the incentive to move towards electricity as a fuel. We will probably be able to do that if we can have a policy framework that is aimed at making electricity cheaper than gas for the consumer. “

Chris outlines some of the challenges of a carbon tax and why a carbon tax and dividend may also not work.

Chris ends on advice on to think about climate impact and future projects.

Listen below (or wherever you listen to pods) or on video (above or on YouTube) and the transcript is below.

Transcript (only lightly edited)

Hey everyone. I'm super excited to be speaking to Chris Stark again on the podcast. Chris is the Chief executive of the UK's Climate Change Committee. The committee is an independent statutory body which advises the UK and the devolved governments like Scotland and Wales on emissions targets and preparing for and adapting to the impacts of climate change. I think he's one of the most important and thoughtful thinkers on climate change policy today. Welcome, Chris.

Chris (00:32):

Hi, Ben. And hello to the listeners again.

Ben (00:36):

How does it matter that we will pass 1.5 degrees? Some climate scientists’ model that we are likely 90% chance the world will move past this 1.5 C as a point estimate, but also many scientists are communicating and pointing out that doesn't mean we should stop our efforts. Social scientists has also weighed in and have said this 1.5 degree has a lot of communication and political roots to it rather than also just some of the science roots. How do you think about these temperature alignment numbers and how this interacts and how we should be thinking about policy?

Chris (01:12):

This is so complicated, Ben. The kind of core of what we do really is defined in the Paris agreement. So for those of you who don't think about this stuff as regularly as I do, there is a global treaty on climate change which was finally reached in Paris just a few years ago; 2015, I think. It talks about temperature goal of keeping global warming above where it was pre industry when we started burning fossil fuels to well below two degrees centigrade is what it talks about. So that was the kind of goal that many policy makers had in their mind prior to that Paris Summit when it was agreed. But quite later on in the process, this extra temperature target of 1.5 degrees was thrust into the discussion. And rightly so, I think, but it was a sort of stretch goal. So can you keep temperatures even lower than the two degrees that most people had been thinking about as a sort of global goal for this?

That led then to this other really amazing piece of work brought together by the UN's scientific cleaning house; the IPCC. Looking at just what it would take to hit or to keep temperatures to that 1.5 degrees centigrade target, it led some of the key stuff that we now take for granted like net zero being an important goal to reach globally, that for net zero CO2 you need to get there by about 2050. They've become really embedded in the discussion now. This 1.5 degree centigrade target has become, I think, a catchall for all of that. It's the target we should be aiming for.

When the UK hosted the Climate summit in Glasgow, it was the 1.5 degree summit. It was the kind of catchall thing that the US and the UK together were really pushing for. The trouble with it is it's really bloody difficult to get to that kind of ambition and it is very likely that we will go beyond 1.5 degrees centigrade. In fact, I will say confidently that we will hit 1.5 degrees centigrade. In fact, the only uncertainty is whether that's as far as we go. The chance of reaching something lower than that is probably now gone. 1.5 degrees itself gets further and further the more that we don't have rapid emissions reductions. Broadly, you need to have emissions by the end of this decade if you'd really think you want to be on track for that 1.5 degrees. And that's a global goal. Of course, global goals are harder than national goals or goals at the level of any single corporate or individual. So it's very difficult.

The two degrees centigrade goal by the way, is very much on the table. My own view--and it's a personal view, is that I think we will keep our temperatures to that because there's all sorts of good things happening in the energy market. But this question of what you do if it looks like 1.5 degrees is sailing out of view is a really critical one because each COP comes around each year, it becomes more obvious that 1.5 degrees is harder. I don't think I have an easy answer to that question of what you do as it slips out of view really. My view is that we stick to it really. That 1.5 is still a useful thing, a useful framing device because it's a temperature goal but it's also this catchall way of describing the need to throw everything at it. That is still useful to talk about that.

And if it's not 1.5, then we go for 1.6, and if it's not 1.6, then we go for 1.7 because every fraction of a degree matters. Every fraction of degree causes misery and cost to the economy becomes more difficult to manage. We get into quite difficult points as you reach the very much higher temperatures where it's quite difficult to describe the impact because they're so catastrophic. But one more thing on this, Ben, there isn't some special significance to 1.5 in the literature of the impacts. It's a temperature. It will come with costs. There are awful things that will happen to the natural world at that kind of level of temperature increase but it's not special. It's not particularly a special target.

One of the things that often is pulled out of the lecture is that coral reefs are quite likely to bleach more extensively above 1.5 degrees centigrade. Why do we obsess about the coral? Well, partly it's the visual metaphor of it, but also it's because it's one of the very few natural systems that we think is then genuinely impacted above 1.5 degrees centigrade. The point is that it's a slightly artificial threshold. Basically the goal here is to keep the temperature as low as we possibly can. And actually the trouble with all of this is that the communication of that is really difficult as probably I'm showing you today. It's not an easy thing to talk about keeping something that hasn't happened yet as low as possible. That's how we've got to work and frame it and work hard at. So that's the challenge. I think we're probably going to have to come up with a different framing technique than 1.5 degrees centigrade. But 1.5 has been very helpful in pushing the progress that we've seen in the recent years.

Ben (06:36):

Yeah, a very useful simple message. Thinking about the coral reefs, climate warming is happening now. Coral reefs are being bleached at this moment so that's why it's a very apt metaphor. But what you said also echoes what you said last year and my conversation with climate scientist, Zeke Hausfather, who makes the same point. It's not a point estimate. There's nothing particularly special. It's a sort of spectrum. Different parts of the world have different things on averages and all of that and you kind of want to aim for as low as possible. I guess the silver lining out of some of that is if you look at maybe where the estimates on climate policy were 10 or 20 years ago. Maybe even 10 years ago, it looked like a four degree world or above was a significant probability.

Whereas if you look at it now-- Again, you have to execute on the policy. And we can talk about the differences between implementation and ambition. But if you look at the ambition, most of the models are pointing towards between two and three. 2.7 is a median that I'm looking at. Two, like you say, is actually very much still on the tables and there's error within that which is the silver lining. And again, it's a really nuanced thing to say you need to be able to on the one hand celebrate that you've gone from four degree at your mean estimate, median estimate to 2.7 because that's progress. That's good. You don't want to discount the fact that we've done something. But it's not below two and it's not as low as possible. So you've kind of got those. I think people sometimes lose hope or whatever that is if they feel there's no progress being made. But you also can't be complacent. So the messaging has got trickier.

Chris (08:15):

It has. You put that very well, I think. As we went into the Paris COP before this global accord was finally agreed, we were facing best estimate then. The con-central estimate was 3.6 degrees centigrade of warming by the end of the century. And now today, as you see, a relatively conservative estimate of where we stand is if you add up all the pledges that we've seen in the cut process, it's something that's about one degree centigrade less than that. Now, that progress has been achieved in less than a decade. I think that is progress. People should be angry about the fact that we're in this position, and I understand that. So we've got to keep that process going. I think the 1.5 degree framing does help with that but it is very lightly to slip from view. I think we've got to be realistic about that.

Ben (09:08):

That's fair. Your climate change committee have produced some really excellent reports over the years in my opinion and a lot of people I know. So you've had quick hits post COP conferences to work on voluntary carbon markets, this really big piece on adaptation, and of course assessing the UK government's strategy. I'd love to touch on many of these, but it might be worth highlighting on the COP things. We last spoke about the Glasgow COP26 being a corporate and finance COP to some degree and that businesses and corporates as enablers definitely seemed to come to the fore as an idea. My outsider's impression of the COP27 in Egypt, it was perhaps a little bit more niche and targeted and was looking at maybe more of the developing world. What did you take away from the COP in Egypt and how have things changed over the year?

Chris (10:06):

I find Egypt COP really interesting. I didn't go to it. I have slightly regret not going to it; not because it was a really interesting place to actually go. I mean, a lot of horror stories about some of the things that happened at COP this year; accommodation wars and lack of sanitation and food and those sorts of things. But the reason I regret going to it is because I think it was right at the crossroads of a whole host of stories, some of which you've just talked about, Ben, and it's not quite clear to me what the theme really was in retrospect to that COP. So you had this ongoing interest from the UK and the US particularly to push what we call the mitigation agenda. That is the need to cut emissions which is a big part of the story. It's what we often look at in my work in the CCC and what we're best known for as work on net zero.

But actually for many countries in the world, what happens on emissions within their own country is not that important to the story of climate change. What they are grappling with is the impacts of climate change itself which are largely outside of the control of some of the smaller countries. So this question of what you do about that really came to the fore. There has been several attempts at getting something called loss and damage onto the agenda at COP. COP happens every year. It's always hosted by a different country. There is always a push to discuss the kind of reparations as it's sometimes called that are due to some of the countries that are experiencing the worst impacts of climate change but had the least to do with the problem.

Each year it's raised and then sort of taken off the agenda at some point. So scrubbed before the final agenda is agreed, usually. This year that didn't happen. It remained on the agenda all the way through. And then remarkably there was an agreed text which included the words loss and damage and this idea that there should be some sort of facility in there which is really a kind of UN code for transfer of resources from the richer economies that have been largely to blame for the problem of climate change, and those poorer economies often in the global south that are now experiencing the worst impact. What's interesting is that these meetings each year are really hard going. So you get this moment where loss and damage gets put into the text and agreed, but there's no money behind it. So the next COP then has to work out what the money behind that looks like.

Those of you who follow this will know that there has been for a long time a discussion of what's called climate finance which is a really bad term; very difficult term because it doesn't really describe the finance challenge in my mind. But this idea that there should already be a hundred billion dollars of climate finance largely coming from those rich economies to help with the issues of climate change and decarbonizing and all the other things that need to go on. And that a hundred billion dollars was a figure that was being discussed back in the Paris COP and still has not been met. So we're in a world where it's quite easy to get these things agreed or the effort is there to get the text agreed, but the money behind it is a much more difficult thing. And each COP, it becomes more and more difficult I think to get the financial facilities agreed.

So that's how I'll think of Egypt as this sort of struggle where you got this kind of push still from the western economies to talk about a mitigation and 1.5 degrees centigrade in the UK sort of outgoing COP presidency prior to the Egypt COP saying 1.5 got to stay on the agenda. And then this kind of really interesting and pretty successful movement from the African presidency to get loss and damage on the agenda and successfully landing the idea that it needs to remain there. So it sort of sets up the next COP and the ones after it to now have to tackle these things together for the first time. I think in the end it was about as good as it could be actually. The next COP is particularly interesting because it's in the United Arab Emirates and it'll be another COP talking about energy issues. So really interesting to see what happens next.

Ben (14:25):

I think we spoke last time about this sense of fairness being one of the major political economy issues to deal with which has no simple resolution. I have to say post pandemic, I got a little bit more negative on it in the sense that if you had a benign rational dictator of the world, it would probably be obvious to that entity that some sort of fund which would've funded Covid vaccines or treatments for the whole world would've been a great net benefit. And that was kind of quite clear over a pandemic. Climate's actually more complicated. But the root of that problem about where you have the resources and how to allocate it seemed to me to be similar and you couldn't get richer nations easily agreeing on that, although they all agreed kind of in the messaging and in principle.

Having said that, it's a longer going process and it's still being worked upon and it does seem to have a little bit of progress. So there is a little bit of silver lining. But I do wonder about that particularly with where everything's going on in the world. That just at this moment in time nations have got a little bit more inward looking as opposed to global looking. But it does change with the times and can change quite quickly. And in history particularly if you're looking at five year or 10 year periods, it has changed quite quickly.

Chris (15:42):

Yeah, I very much agree with that. Markets need to come into this discussion. I think the framing that I've often put around this is that we are going to have to tackle climate change in an increasingly divided world, at least for the immediate term. This multilateral approach that the UN is just about holding together on climate it doesn't do much to hide the divisions now that you see across the world on some core issues; not only the energy issues. I think what points in the favor of good things happening, I suppose is the fact that the market dynamic has been harnessed on energy at least. That you've got this one way directional thing now happening on energy that points away from the use of fossil fuels towards a cheaper cleaner energy system which is irresistible in the end, I think. So that the markets in the end pull you along that way. But that's the mitigation story I talked about, that's about cutting emissions. It's much more difficult to consider and work out how you can harness markets on the adaptation side because it's fundamentally more difficult to monetize adaptation benefits if your adapting to climate is often not such an obvious return to investors for the big upfront capital investments that are required. So it's tricky.

Ben (16:59):

Yeah. So the adaptation piece where you've done a really big report recently I'm definitely going to touch on that. But perhaps as a segue into that would be maybe thinking at that corporate business level, particularly on thinking around net zero or net zero commitments. So I'm hearing debate about the value of corporate net zero commitments or not, and particularly so-called scope three commitments. So for listeners, scope three is often considered outside the control of companies. That's maybe one of the easiest ways of thinking about it; whether that's downstream or upstream. On the one hand, some people argue there is signaling power and corporates can direct strategy and cash flows to be part of the solution.

On the other hand, corporates do not have direct influence over the power grid where they take their energy from. So you want to be on a green grid, great, but you've got no influence on that. Perhaps they can influence transport or fleet and maybe heating to a degree, maybe land use if they got supply on that. And some also critics worry about greenwashing. On the other hand, at a sector level and on country level, net zero and that kind of thinking seems to make quite a lot of sense. I guess there’s some climate economists who also question about this carbon budgeting on a corporate level. The econometrics don't hold up as well versus a sector or a country level. So how do you think we should be thinking about net zero at the corporate level and maybe some of your worries or pros and cons about the situation?

Chris (18:27):

I've got lots of worries but also some positive things to say about the recent move towards all of this in the corporate community. It is worth just stepping back from this. The discussion that we are having about corporate commitments to net zero is completely remarkable. We would not be having this discussion five years ago. So something has shifted in the corporate community that has meant that there is now a need, I think, whether it's for reasons of social license or whether it's-- I think probably a lot to do with the fact that if you want to hire good staff, particularly young staff, you've got to have solid climate commitments in place and customers are looking for that too. So what we have now is in one sense really, really good.

We've got a lot of very strong and I think legitimate commitments to achieving net zero at corporate level. My concerns come from mainly the fact that it's actually very difficult to define how most corporates get to net zero unless you are an enormous multinational. I'm going to make a notable reference for a corporate like Microsoft which is way ahead of this as a really good plan for not just reaching net zero, but also getting negative and actually undoing some of the harm that has been done over the time that they've been using their energy particularly. That's great. But for most corporates, they're not in that kind of position.

So you see this kind of rush to adopting a net zero target often with a date and often that date is ahead of the global goal. That's kind of what you want really. You want corporates to be aiming for something that is more ambitious. Some of those dates are pretty punchy to put it mouthy. 2030 is a common one. Often you see 2040, some of them are even 2025 astonishingly. But actually if you look at how those will be achieved, you need to look through as you call them the scopes-- and I won't go through all this. But as you move from scope one to three, you have greater agency at the lower scopes to actually tackle the emissions that you are responsible for. Scope three is mostly what's happening in the wider supply chain that you are interacting with. It's difficult at that level to know where to draw the line and about what a good target should be.

And interestingly as we've looked at this, we start from the principle that net zero for a country like the UK will require lots and lots of corporate investment, lots of corporate support. In fact, most of the work that we will do as a country to get to net zero will involve investing at the private level. It's not going to be driven entirely from public investments. So you kind of want those corporates to be on side with it. So why am I concerned about net zero targets? Well, I'm concerned that at the moment you've got this rush to achieving net zero, but a rush to do so in the wrong way. So you've got corporates thinking, "Bloody hell, we've made this commitment. How can we do it?" They work out what those scope one to three emissions are and they find actually that they've not got a lot of scope to do much on many of those things and they'll do cheap stuff first. So they might put solar panels on the roof of buildings. They might have better travel policies for their staff.

But then they'll find that's not reducing emissions very much and then they'll turn to offsets. And this is the key things. You've got lots of very cheap offsets out there right now-- very, very cheap offsets, mostly forestry offsets and they're legitimate things. People are buying them I think mostly in the knowledge that they are useful things and want to be able to legitimately say that they're part of the answer. But they're so cheap and they're cheaper than the harder things. What you really want to be able to say to those corporates if I could sit them all down is, “Thanks for setting out your ambitions for net zero, but let's just talk about your place in the system.”

So mostly-- your emissions if you're a service sector dominated economy like the UK, mostly your emissions are connected with the energy that you will consume in buildings. Most of those are about the electricity that you might consume. And in that world you might think it's a good idea to put some solar panels on your roof. But I'm going to tell you, “No it's not.” It's quite interesting, it's not. Because in this country, in the UK, we'll probably have fully decarbonized para system over the next 10 years or so. In which case plan for that and make the harder steps now to decarbonize the fleet of vehicles that you use or to heat those buildings with a heat pump rather than a gas boiler. That tends to be more expensive and-- this is the crucial point-- it tends also not to get you to net zero today or indeed any time over the next decade But it's much, much more useful for the country and for the global effort if you do those things.

So it’s really interesting for every corporate out there that's got a net zero target. What I would like to see is some kind of kite mark, if you want to call it, for having a good transition plan. Something that marks you out as a company that is doing the best possible things now as part of the wider system change that a country like the UK or the US or the whole of Europe or anywhere in the global economy; as part of that system accepting some of the conditions in that system and recognizing that certain things along the way will shift outside of your control. If you get to that kind of world where actually you're getting more credit with investors, credit with customers, credit with your staff for being net zero aligned than for being net zero itself, then I think we'll be in a much better place because you're going to get a much better alignment from the corporate community behind the national goals that we have here in the UK for getting to net zero.

Ben (24:05):

That's really fascinating. I guess in investment world there are two pseudo kite marks but that don't really capture what you just articulated. So they would be what people use with CDP and also what people use for this science-based targets initiative; SBT, which look probably more primarily at carbon footprinting and glide paths. I really simplify something but they don't really capture what you were talking about. So I think that's quite interesting. I don't know whether you think those have some kite mark value or we really need something else which takes into account of that. And that also puts into question partly this value of carbon footprinting itself at a corporate level, but particularly at an individual level there's some interesting critiques about how that came about. Sector and national, yes, because the macro pitcher gives you good information. But I think people can't comprehend that even the largest company in the world is just a microcosm of what normally a rich nation would be. But how should we think about carbon footprinting and do you think any of the kite marks that you might know about do encompass maybe a bit of this more so there's room for another organization to really look at that?

Chris (25:24):

There are lots of really good organizations out there doing good work. SBTI that you talked about, the Science-Based Targets Initiative is one of the best ones. I think one thing, in the end they all need to come together and align behind some sort of accounting standard. That's the real goal here. So getting to a point where this is just a normalized thing is really the goal here and that kind of idea that corporates need to be net zero aligned rather than net zero themselves is very much at the heart of things. I think if you get that accounting standard in the right place then it'll just be done as a matter of course. So I think it's very important. Carbon footprinting and the assessment of it is hugely important so I don't want to undermine any of that trade. I think it's very, very important the tools that you will need to understand the impact that you're having on carbon are really important. I think what we lack is the next stage of this which is a sort of intelligent, informed discussion about what that's telling you.

So I had a discussion this week with somebody who works in the health system about the extent to which-- even in the NHS they really are thinking about this. But you've got pockets of the NHS… NHS is quite an interesting one because you've got lots of people worried about climate in the NHS. Very often find that actually in my trade that it's often doctors and nurses that are most concerned and come to me with questions about what to do about climate change.

So you've got pockets of the NHS just as an example, where they've got to the point in their carbon footprinting, where they've got this incredible understanding of the carbon impact of a particular operation in a particular building and you sort of wonder what is that actually teaching us? We've gone almost too far down the route of thinking about that whereas some of the fundamentals are being missed. Most hospitals, most NHS buildings are being heated with fossil fuels. That's a much bigger impact. But I think this speaks to the idea that we're all grappling around, we're all looking for something that we can really get our teeth into. So I think the more that we standardize this, the better, but there's still a bit to go on that.

I should declare an interest in this because I've been chairing one of the work streams for this piece of work that is commissioned initially by the treasury in the UK to look at coming up with a transition plan standard that could sit alongside some of the work that's been done particularly in the financial sector. So GFANZ which is a thing that may be known to you, this Global Financial Alliance for Net Zero is coming up with all sorts of very interesting ideas about how you align the right finance behind the green stuff. This is a sort of equivalent to that really that takes it into the real economy and asks questions about how corporates themselves-- particularly in the real economy, but also finance firms can themselves be better aligned so that investors know what they're investing in and banks know what they've got in their balance sheet. We're almost there actually with this. I'm quite pleased with how things are going. It's not easy at this, but we're not far off having some common standards. I think that means something.

Ben (28:25):

So I completely agree. I say a lot about this in overall extra financial data, whether that's environmental, natural, or even to do with the human and/ or the social. That the data is coming, the standards are evolving. You've got a lot of work streams, international standards accounting boards, GFANZ and all of that. But even today with the data that we do have, I can see the missing pieces to your point. The kind of analysis of it or what does it mean or what can you do or have you missed the whole-- there's a lot of this in your reports, the whole enablement piece. I always talk about, "Well, if the world is electrified, you're going to need a lot of semiconductors."

So you want to make your semiconductors well, but regardless of how intense they are, you're going to need vast more quantities of that. You might argue the same for copper and lithium and the like. Those are very obvious ones and there's a lot of unobvious ones. So I think we need to invest the time alongside of being able to interpret the data and tell us what that really means as well as having it. It's coming faster than it has ever been because financial standardization or financial data took quite a long time and it's actually happening much quicker within this area than I've ever seen. Even though it does seem sort of slow because it has taken years and years, it's still happening. It's happening faster.

Chris (29:49):

Yeah. But don't forget the bigger challenge beneath this is not disclosure, it's actual action. Perhaps I've been swept up in this over the last few years as well. Is this idea that if you just get the disclosure regime right, everything will click into place. Slightly ignores the fact that there's a lot of big stuff needs to be invested in and the disclosure regime is there to make sure that when that happens you should get good credit for it. But I think sometimes we forget that last bit and are being overly focused on the standards themselves. My worry with that is that you can really get in-- And again, I think I've fallen into the trap of doing this over the years. The minutiae of this is just there's never an end to it. You can fall endlessly down the rabbit hole. I worry that for those of us who are turned on, it makes sense. But if you are brand new to this thing wondering why you have to disclose all this stuff or follow some sort of counting standard is it is byzantine in its complexity and it will not be obvious why we are asking for that kind of level of details. So we've got to stick to the really important principles I think at this stage particularly.

Ben (30:57):