Once upon a time I went to visit one of the most remote people on this planet. These people were called the Wana tribe.

Today, they are a semi nomadic hunter gatherer tribe who are transitioning to some forms of agriculture.

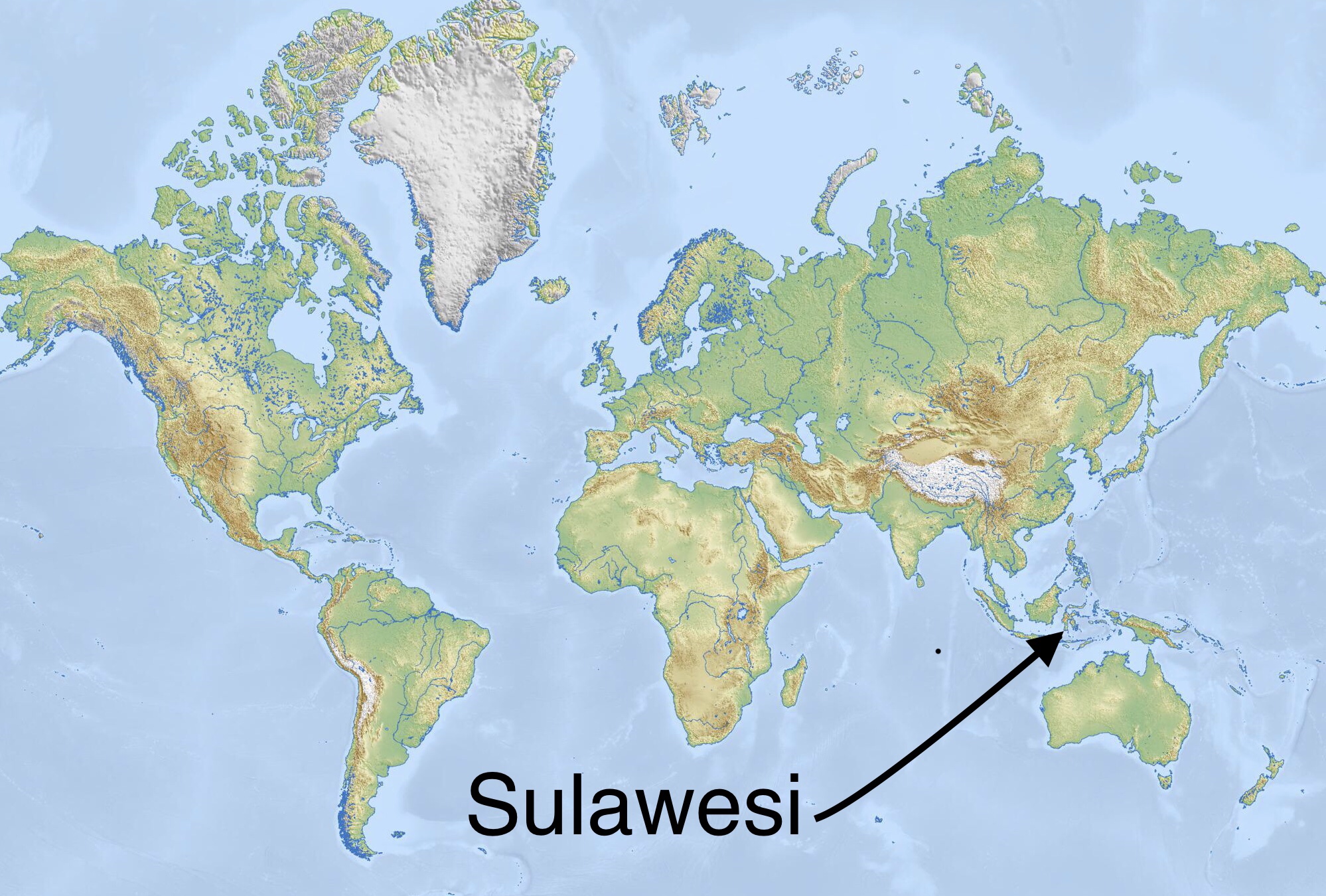

The tribe I visited lived deep in primary rainforest jungle in the middle of an island called Sulawesi, part of what we call Indonesia.

Map showing Sulawesi part of Indonesia. Shapes a little like a starfish.

That visit and my previous visits to India and Borneo and northern Thailand caused me to reflect on several (mis)conceptions that I still observe today.

Approx where this Wana Tribe live

We (being richer, dominant, more educated) know better. We believe people make “poor” decisions because they are not really “rational”. (What’s the point of a pension if you are likely to die before 65?)

That certain of our cultural myths and standards should apply to others. That the standards of the present apply backwards to the standards of the past.

That many of us really have not much of an idea of what it might be to live in extreme poverty with no running water, no toilets, no secure food, no secure housing.

What a “romantic” view of an indigenous people might look like that: although their land use is more harmonious, it’s a hard life even if it’s much less dense in land use.

It was a long time ago, now, over 20 years for me. This reflection is based on notes from my journal.

I remember that it was hot. Humid sticky and hot.

Buffalo sacrifice in the Toreja lands

I had only a few days ago come from a culture of ritual buffalo sacrifices and great summer festivals. (Another story).

It was 1998, in the middle of my third Asian adventure (after Borneo in 1995, India in 1997) and before the fall of President Suharto.

There were mild simmering tensions between the racial Chinese and the non-Chinese, mostly Muslim, but nothing had yet exploded. Sulawesi’s population had mixed heritage. There were influences from the Dutch colonialists of over 300 years ago and Christian missionaries.

Sulawesi is home to a lost civilisation. A few stone idols reminiscent of those in Easter Island all that remains of an ancient culture older and unconnected to the one sitting on those lands today.

All of this is mostly divorced from the Wana. The Wana tribe have lived their own lives in the jungle with only the occasional trade of resin with the outside world.

We had to go and meet them in their territory.

We had a Guide. This was more than vital as within a few minutes the jungle absorbed us and we had no idea where we might be.

Manuel our guide. Note new Swiss watch on wrist. (c) B Yeoh

Our guide was Manuel. We thought he used to be a ranger, at least part time, and had helped establish some trading. The Wana supposedly had always traded resin from the jungle but until recently hadn’t settled. Supposedly, only a few years ago the tribe had worn bark clothing and little from outside although that had changed.

We brought useful tradeable items to exchange for our stay with the tribe. Aspirin, clothes, foods (instant noodles were storable, quick to cook and seemed tasty) were more treasured than “money”. The Indonesia Rupiah was a new myth for them and brought no value.

Money was of use to Manuel and we bore a tradeable item. We had an unwanted Swiss watch, I forget the brand, but it was mid-priced of the type you might receive as an unwanted 17th birthday present (can be seen in picture). A relatively unique item for the area, we part-traded it for his services. Extolling the brand and reputational values of Switzerland, which we pointed out on a map.

Cultural exchange was common. Everything took a while to do - at the shops, at the bus, walking down the street - are you Japanese? Chinese ? You live in England ? You born there ? What is Princess Diana like ? Have you met the Queen ? (The British Royalty being pretty much the only export to Sulawesi the UK had in 1998). What do you eat ? What is London like ? What do you think of (insert place) ?

Luckily, basic Indonesian is an easy language to pick up. My brain still had enough fluid intelligence to pick up enough to have decent conversations and a dictionary (these days were the early days of the internet and while Internet cafes existed they were rare).

We readied our wares and headed out to the Morowali park entrance.

The initial part was by boat. We skimmed across the water. No humans in sight. Mangroves. Water. Sky. Jungle.

A bamboo crossing. Yes, I was a little scared crossing on it. Note the flip flops of our guide.

Manuel didn’t have a back pack. The ubiquitous piece of equipment that marked out the foreign traveller. He carried our equipment by bamboo carrier. He had impressively flimsy foot wear - faded flip flops. This proved to be one above the Wana, when we found them, who were mostly barefoot.

Images of jungles evoked wonder. An alien otherness full of tactile shining greeness, the pictures hypnotised us.

The reality was visceral but remarkably different. Hot, baking hot. Humid, an immediate sweat-inducing drenching dampness.

The rainforest was noisy. An intermittent cacophony of sounds, to my ear there was a background layer of insects, so wide a variety they would always remain unknown.

This was punctured by the percussive movement of larger creatures and the swishing interaction with the vegetation which seemed to grow before our eyes.

It was fascinating and alien to a city dweller yet soon turned to intermittent boredom.

The vegetation swiped at you from underfoot from overhead from left and right, forwards and backwards. The heat and noise were omnipresent.

Everything was curious and worth examining. Several species lived there and no where else. I could have stayed a whole day in a 50 metre radius and not have been bored. Stopping was not an option for us. We needed to make progress, tramping on so it became a form of endurance and the banal pattern of foot-in-front-of-foot only broken by yet another quasi-spectacular sight: a large poop from a jungle cat (pretty rare), a complex spider web; vines you could cut water from (Manuel pointed this out in case of emergency; stay by a water source and hope the rangers come and find us); poisonous things, spiky things; enormous ants.

That’s pretty much why I have few-to-none pictures of the jungle depths. I was carrying black and white film. I wasnt going to waste any film on greenery. I think I have a handful on a contact sheet somewhere, but I haven’t managed to pull them into a digital archive. Not until recently has the technology been cheap and swift to scan at enough detail, and my negatives are sitting in a show box somewhere.

This is a glimpse of someone else’s trek in that same jungle (pict)

Five hours in, we came across two Wana fishermen, right in time for lunch. We had a meal with them. Looking back, I wonder how strange it might seem, these complete strangers emerging from the jungle to share a meal. I don’t know what Manuel would have said and I haven’t noted that we spoke. Even if I had the words, a place like London would be challenging to describe. We ate freshly smoked fish both barbequed and in a stew. It was delicious.

We set off for more walking.

We make it to site. There were no Wana. I noted in my journal: “Nomads! Darn, Wana”

The Wana are semi-nomadic. They up and leave when they feel they have taken enough from their site. (Typically every 3 years or so). Although the tribe I visited was possibly transistioning to a more permanent village structure - I had the impression when meeting them later that maybe they hadn’t fully decided.

Manuel wasn’t worried. He gave the impression that this site was still used by hunters from time to time and it was quite possible we wouldn’t see any Wana here but it was too far to make it to the main village site in one day.

I recall being moderately concerned as I wasn’t sure this was the deal he originally suggested, but I suspect we were never going to get to the village in one day.

Manuel took his machete and cut down segments of nearby bamboo. You could fit an apple in the cut out segments. Manuel showed us how they made a makeshift pot to boil water in.

We had water-purifying tablets with us. We used them and boiled water for several minutes to be sure. Water illness could kill or hospitalise us. We brought instant noodles (chicken flavour I think, a little yellow paste of mono sodium glutamate and flavourings) which after hours of walking tasted somehow amazing. The bamboo made chop sticks for eating and my respect for this fast growing renewable resource has remained high ever since.

Regular chores and activities were laborious. Toileting, finding a suitable place, covering; making fire, cleaning, washing - all these functions taken for granted at home take significant time and effort.

There is a notion that in the quest to raise living standards by developed nations standards, we are destroying nature and traditional ways of living, to the detriment of affected cultures. Part of this narrative is true, in the sense that our destruction of trees and forests continues and that European nations, at first contact, brought much death, disease and destruction (for instance, in Australia and in places like Indonesia). The Wana way of living is in one sense less intense and more harmonious with their environment. The Wana have stories and shamans, they play in leisure time, they wake with the sun and sleep after its setting. Despite all that, Wana life struck me as hard. There is food, but they worked hard for it. Items and chores we take for granted, they spent a great deal of time and effort on.

We borrowed the raised huts for a roof and we had our sleeping bags but there was no running water. Buzzing insects and the night time noise of the jungle - often more noisy than the day started from sun down around 6.30pm. I played a game of hang man by candlelight, my first proposed word was “lynx”. I’ve always played to win.

The sun rose and rose us. There was not much changing, I prefered to sleep in long clothes to reduce mosquito attacks. There was a routine for toileting but who would bother with make-up and tooth brushing?

It was a few hours more to the village and we travelled what Manuel saw as a path, but I saw as simply jungle.

We arrived. The Wana are unsurprised and cautiously welcome. They indicated that they see a handful of tourists a month and there was a routine of sorts for treating us. We spent the rest of the day and the next half day hanging out at the village.

The man on the left is an elder, the women are preparing the bitter local root. (C)

The routine for tourists (or maybe we deserve the more authentic sounding title of “traveller” as we had brought items to trade and stories) started invariably with the blow pipe (see picture top).

After dinner, dishes are cleared and the family sleeps in the same space.

The Wana still used this very skilfully to hunt. A hapless tourist stood a slim chance of hitting any target and only a moderate chance of shooting a dart out properly at all. Still, I dutifully attempted a shot and posed like a well-behaved tourist.

The Wana had started cultivating some fruit and vegetables although hunting and gathering were still a large part of their diet and day. I asked to try the local food. The women were hard at work preparing it and the translation was that it was a type of root vegetable like cassava.

It was deeply bitter and fairly disgusting. My face revealed this to much amusement from the women. With chatterings of “we told you you wouldn’t like it”. There was only simple conversation in English/Indonesian as Wana linguistics were tough.

I tried to ask whether anyone from the Wana would leave and I think I received a reply along the lines of “where would we go?”

Cigarettes both clove and western had already been brought to the village and were valued by children and adults alike. The girl on the right wasn’t part of the boy gang.

The children were at turns shy and curious playing a peeking hide and gawp. The boys more assertive and keeping to themselves more. Smoking was a cool behaviour. One boy was making a toy.

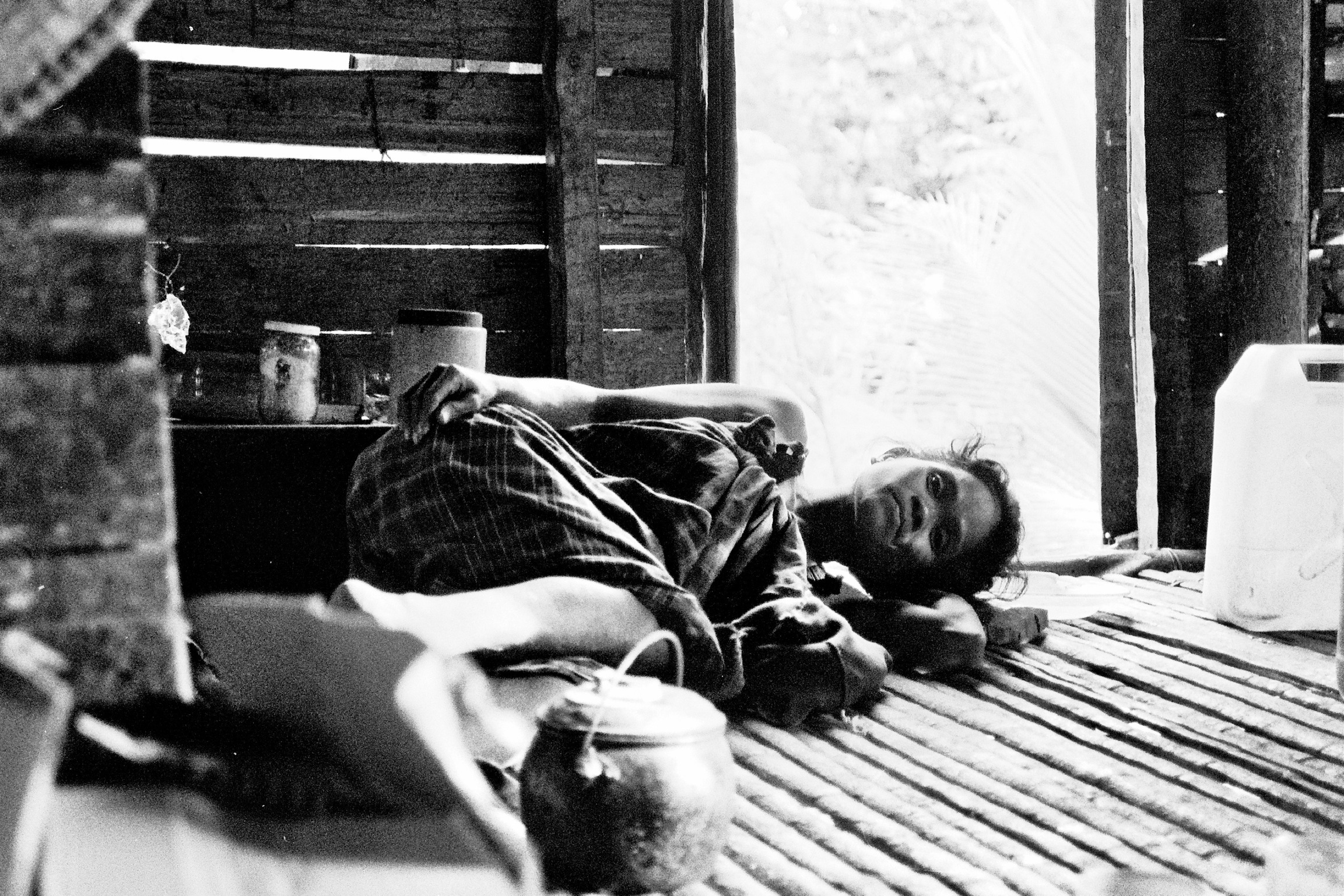

After finishing the food preparation of a couple of hours, there was lazing about and mild gossiping waiting for men to arrive for the meal.

The maleo egg. Sunny Side up. Note the very large yolk. (c)

As an honoured guest having brought useful gifts, I was offered one of the local foods. This giant birds egg. The size of a small melon or grapefruit. It was served in a sunny-side up type of way and for an egg lover like myself, it was delicious: yolky, creamy, sweet.

Later, I found out this was the egg of a maleo bird. A rare bird that only lives in the Indonesian jungle with perhaps around 10,000 birds left. (I note collecting eggs in some parts of Indonesia was only banned in 2004).

The maleo buries its eggs in the warm sand by the river banks. It thinks to fool predators by digging many false holes. This work fails to trick Wana who simply watch until the real egg is laid. The egg is so large with a sizeable yolk such that a baby maleo bird can almost fly from shortly after birth to help it escape predators. I think it’s likely I remain in a small group of only a handful of humans who’ve ever eaten a maleo egg.

Despite the hardships, I don’t think I would have said the Wana were much unhappier than many peoples I have met.

Although, what happiness? (Eudomonia fufilment, or hedonistic joy?)

Did the Wana work more or less hard than a city dweller? I’m unsure. There certainly was much hard work associated with daily living and I couldn’t say for sure on the work/leisure split.

Accidents and health problems, I could see were very dangerous. Small injuries could be fatal. Diets and food supply were not secure. Sanitation was open. Clothing was not well supplied (I was told then that until recently it was mostly made from bark) although the weather meant plenty of clothes were not necessary.

(To me the observations on food insecurity anecdotally back up the “gorging gene” theory. Supposedly, our hunter-gatherer forebears opportunistically bloated themselves on sugars or fats as food supply was insecure. I could see that would be a good idea for the semi-nomadic Wana, particularly pre-tourism)

The Wana had few artefacts and items. The blowpipe was noticeable. The huts had pots and the like but nothing like you’d see away from the jungle. It’s a stark contrast to our consumer and material world. Wana stories are still told orally. There’s no schooling and I don’t think the village was literate. I didn’t see a single book.

The Wana children were curious about my pens and pencils and one child drew a circle in my journal. I tore out several pages to give to the children. I made a flapping origami bird (useful travelling party trick) that was a delight.

I could see that privacy, as we know it, was rare. Families and extended families slept together. Manuel our guide slept with a Wana family and we had one of the only spare outlying stilted huts.

Children would sleep with parents until they were going to move out. As speculation, I wonder if perhaps part of this is more hardwired today than we might imagine – like the gorging gene. It would seem to me that if hunter-gatherer bands were always this intimate, the instincts of some children to want to sleep with their whole family for some time may be built-in. (The extremes of co-sleeping are laughed about in Western society now, but it is commonplace in many other cultures and countries).

The Wana had skills and knowledge that surpass city-dwellers in many respects. I could see that most acutely through the blowpipe but even in their knowledge of the area, the gathering and hunting techniques, and the like. There was enough resource for Wana to typically stay in an area for a few years before moving on.

I believe there is debate on what ancient humans may have done, when we were all mostly hunter-gatherers. Some tribes probably roamed constantly. Some like the Wana were likely semi-nomadic. I didn’t hear the Wana origin stories – I have since looked a few up, there are not many anthropological studies on the Wana – but they have their own tales.

Knowing what we do about various societies and cultures today, it strikes me that there must have been thousands and thousands to hundreds and thousands to maybe millions of complex cultures like the Wana. I’m inclining towards what Harari (and others) suggests in Sapiens that Empire and Religion and Money have been substantial unifying forces – and I could see that in the way the Wana have mostly avoided all three of these forces.

They had their own culture. Money was not useful to them, trade and barter was better and the empires of the Dutch etc. had passed them by.

Now there is a small tourist trade and I believe a battle over land rights with the Indonesian government.

These people would likely be classified as deep poor although until recently money would have been mostly meaningless to them. I can see how some benefits of secure food and health would be very valuable. A literacy to record their stories would I think be useful – although maybe that’s my perspective. Many of the items of a western life, they could continue to do without and certainly not at the cost of a loss of their habitat.

I had a wash in the river. This was the only running water. I reflect now on the amazing infrastructure we have for clean-to-drink water. A piece of life we take for granted.

We trek out the next day. This fleeting visit would hardly be remembered by the Wana. We were moderately welcome interlopers. Our trade gifts useful, my origami paper bird a novelty that probably lasted longer than the memories of us. Did I give as much as I took ? In terms of experience, I took much more – a view on life and a way of being which is on the way out – a set of impressions that have lingered – an insight into what it might mean to be human – how I might relate to this remote and hardly touched tribe of humans – to try and understand what it might be to be human – to be understanding of how others might live – to not take the challenges or achievements of humanity – at least for a small moment – for granted.

More photos below, including their tough feet and babies in their carriers.

Read about one of my only experiences of racism here: https://www.thendobetter.com/blog/2019/3/30/racism-pressed-duck-and-a-family-tradition

Or, a few lessons that autism has taught me:

https://www.thendobetter.com/blog/2017/7/15/autism-lessons-taught-me