Defending the worst attraction in London

The mound gives you different perspective and views

The project nudges to innovation and tries something new

It has potential to raise the debate on green roofs and urban design

It was built quite quickly on a £2m budget

I’ve been to visit one of the worst attractions in London (although I don’t think it’s worse than Madame Tussaud’s) and all the criticism is likely correct.

But I’d like to speak up for the positive side.

It shows that new structures, new things, (a bit) weird things can be built in the middle of London.

Without trying something new, without failing at something, how will we progress ?

OK. It turns out it’s nothing like the London eye but how we would know for sure unless we tried it?

I was there on a blustery Sunday afternoon, and there was a steady stream of people going up and down. We laughed and we wondered.

People will complain about the £2m cost and of course there are more life savings things we could be spending our money on. (For instance almost any investment in Africa regards COVID) But for anyone looking at budgets, £2m is actually a very small amount of money for such a thing. And it keeps a handful of people steadily employed. (I think it’s over staffed but it’s probably health and safety policy).

The mound was built pretty quickly. In a few week, I think. I’m in favour of showing infrastructure can be built at speed.

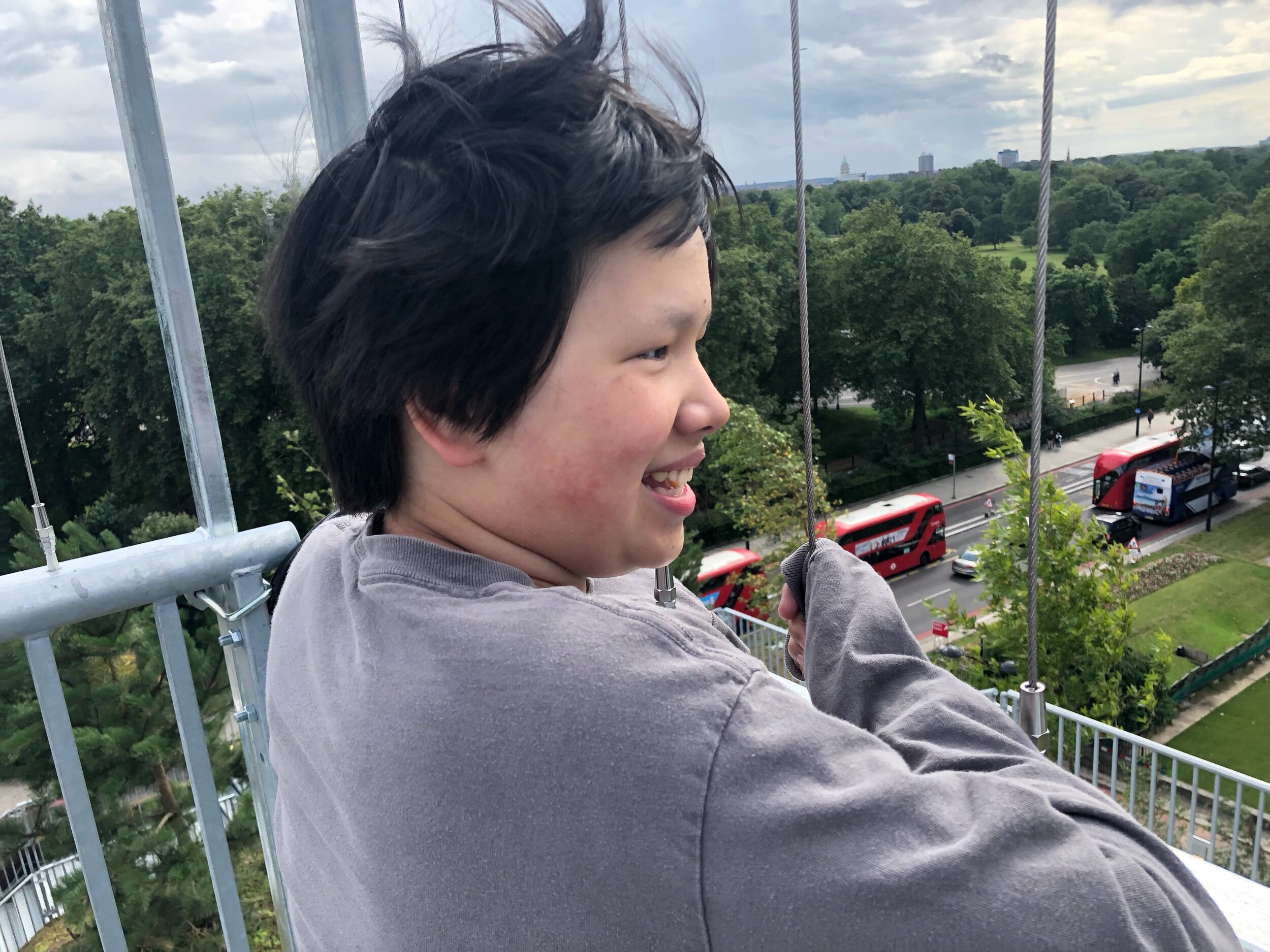

The mound gives you a different perspective. It takes an old area - one which needs change - and it nudges you to view the area differently. The views may not be the spectacular ones wishes for, but still it gives you a different perspective on this important corner of London.

We have particular interests. My son and I. In this, I am led by my son. We ended up spending more than an hour above the buildings, and more importantly above the buses of Marble Arch. Apart from the guards, I hazard that very few people will have take as much time observe=ing the corner around us from such a vantage.

On the grounds of innovation, and that if you never try new ideas to improve then you won’t and on the joys of new perspectives it has given us, I say give London’s worse attraction a try for the views and don’t bother with Madame Tussaud’s.

““We originally wanted the hill to totally cover the arch,” says Winy Maas, founding partner of MVRDV, the Dutch architecture firm behind the pop-up hillock. “That was an interesting discussion, let me put it that way.” Conservation experts advised that shrouding the almost 200-year-old stone structure in total darkness for six months could risk weakening the mortar joints, leading to potential collapse. The solution was to slice off the corner of the hill instead, leaving room for the arch and making the mound look like a computer model caught midway through rendering, revealing the wireframe scaffolding structure beneath.

If the hill’s low-resolution polygonal form gives it a retro vibe, there’s a reason. For Maas, the project represents the fruition of an idea concocted almost 20 years ago, when his firm proposed to bury London’s Serpentine Gallery beneath an artificial hill for its summer pavilion in 2004. It was designed to be supported by a steel frame, rather than scaffolding, so the budget spiralled out of control and the scheme was scrapped, living on in the gallery’s history as the phantom pavilion that got away.

Seeing the Marble Arch Mound a few days before it opens to the public, it’s hard not to wonder if it might have been better for it to remain that way. Architects’ slick computer images have a tendency to paint an optimistic picture, and this is no exception. While the CGI plans depicted a lush landscape of thick vegetation, dotted with mature trees, the reality is thin sedum matting clinging desperately to the sheer walls of the structure, punctuated by occasional spindly trees. The recent heatwave hasn’t helped, but none of the greenery looks happy.

“It’s not enough,” admits Maas. “We are all fully aware that it needs more substance. The initial calculation was for a stair, and then there are all the extras. But I think it still opens people’s eyes and prompts an intense discussion. It’s OK for it to be vulnerable.” The trees will be returned to a nursery when the hill is dismantled, and the other greenery “recycled”, but it remains to be seen what state they’re in after six months perched on scaffolding. It’s a question that also hangs over this summer’s temporary forest at nearby Somerset House, or the collection of 100 oak saplings outside Tate Modern – all of which make you think trees are probably better off left in the ground.

MVRDV were approached by the council after one of its officers saw their temporary staircase project in Rotterdam in 2016, which was a brilliant moment of urban whimsy. Coming out of the station, visitors were greeted with a colossal scaffolding staircase, 180 steps leading to the 30-metre-high rooftop of a postwar office block, from where sweeping views of the city could be taken in. Climbing its steep incline had the momentous processional feeling of scaling a Mayan temple, and it prompted a citywide discussion about how Rotterdam’s 18 sq km of flat rooftops could be used, spawning numerous initiatives and adding momentum to an annual rooftop festival.

Could the mound have a similar effect in London? Will we see the city’s recent low traffic neighbourhood roadblocks swell into miniature mountains? Probably not. But beyond offering a momentary diversion from shopping, the project is intended to raise a bigger discussion about what form the future of this unlovely corner might take.”