Ben Yeoh:

Hey, everyone. I'm really super excited to talk to Rishi Dastidar. He's a poet, he has two books published, Ticker Tape and Saffron Jack. He chairs spread the word. He's also edited a book on poetry craft. So Rishi, welcome.

Rishi Dastidar:

Hey Ben. Lovely to be with you this afternoon.

Ben Yeoh:

Great. So poets always have another job it seems. I think you've talked about this, it's poets slash something else. Like, is this a good thing? Does the richness of life make you a better poet?

Rishi Dastidar:

So yes. So it starts on the basis that there is no way that anyone could make a living from just selling their poems. So there is a necessary need for anyone who calls themselves a poet to have alternative forms of income. Now, if you work towards it, if you're fortunate, hopefully, that the secondary sources of income can be quite closely poetry adjacent. So teaching in a university, teaching in a school, performing, performing your poetry on stage, on screen, possibly even. And maybe even perhaps lending some of your poetry and your voice to adverts, for example. And that's a fairly accepted and a way of being for lots of people who practice and work as poets now as well. My contention is that as an artist [Inaudible]…

…I think it is something in such that it would benefit, there is a benefit to be had from more poets getting that secondary or getting that income from things that aren't necessarily poetry adjacent. So I jokingly suggest slash civil servant, not even jokingly suggest you know, roofing, nursing. I happento work as a copywriter in advertising and branding. So yeah, it's slightly more adjacent than others. But I think it's notable and I think a lot of notable poets have brought those other working lives into what they write and how they write as well. So yeah, I think the model of just being a poet who's largely as academic is only just one model and we should have more models of doing poems.

Ben Yeoh:

Should there be more corporate managers in fact?

Rishi Dastidar:

So this is partly for me because I would quite like to have the title of chief poetry officer. So to any viewers of this who are in a position to hire please do consider me for said role and I will bring magic to all your corporate communications of varying and different hues. A bit more broadly, yeah, I think if you think of poetry as a way of thinking and a way of thinking that is slightly different from one you might get when you're thinking about creative writing, more generally. I think bringing more and different modes of creative thinking into corporate life into business life more generally is a useful thing, partly for giving you different tools and different modes of thinking to get to different results. But also some fundamental level, acknowledging that business, yeah, it's never just rational, there is emotion in it. And it's interesting when you dig beneath a lot of what passes for commentary and talk on culture building, for example. A lot of the thread there is, Oh, these things called emotions, how do we manage those away? How do we channel them productively? That's a very corporate thing to do, isn't it? As opposed to maybe acknowledging them more and actually thinking, how do we actually recognize and use them in ways that might not necessarily be seen as just pushing them out from this domain as fast as possible. And art in its broader sense is useful for that. And I would say poetry is one of those skills and toolboxes that you can actually bring to think about that and start to do that.

Ben Yeoh:

I've read some stuff about some poets being afraid of these Insta poets. Like I'm not afraid of the instant poets, are you're afraid of the Insta poets are there in fact, even Tik TOK poets? I should have looked this up. I'm assuming that probably must be by now, but should we be afraid of the Insta poets?

Rishi Dastidar:

Oh, no. Not at all. So this is a semi recurrent thing that happens maybe every 18 months or so where somebody rediscovers Insta poetry and decides that it is a terrible thing or at least a dangerous thing because it's stuff that doesn't necessarily look like what they believe poetry should be and it has the temerity to be popular and it has the temerity to then crossover and sell. I mean, (Inaudible).

Now, my take on it is, is that Insta poetry is perfectly valid as a type of poetry. I mean, it's slightly odd just even still calling it Insta poetry because after all, you know, the corollary of that would be well, okay no, I prefer book poetry, who says that no one says that. More substantively though, a lot of people's critique of Insta poetry is positioned as an aesthetic critique, you know, this is rubbish, this is a dog roll, this is shit. But actually what's encoded within that is actually something that's closer to an elitist critique.

Because when you actually look at who is writing as to poetry, and of course who has become successful and popular through Insta poetry as well, more often than not tends to be writers, voices of colour from marginalized backgrounds who bypass the more traditional editorial gatekeeping channels to find an audience, to find an audience with their aesthetic, with their poetry, which has happened to be popular. And so it might not be to your taste, that's absolutely fine with me, but please do not think that Insta poetry is the harbinger of the decline of civilization because it really, really isn't. I always hope that people discover poetry that they liked through Insta poetry, but then they discover that there is a world beyond that. If you like Rupi then hopefully you go on and discover other writers who are away from her different from her as well. Insta poetry as a gateway drug? Yeah, I like that.

Ben Yeoh:

So actually that leads me on to do you think poetry, British poetry on deep global poetry then, have this challenge of a diversity of voices and what should we be doing?

Rishi Dastidar:

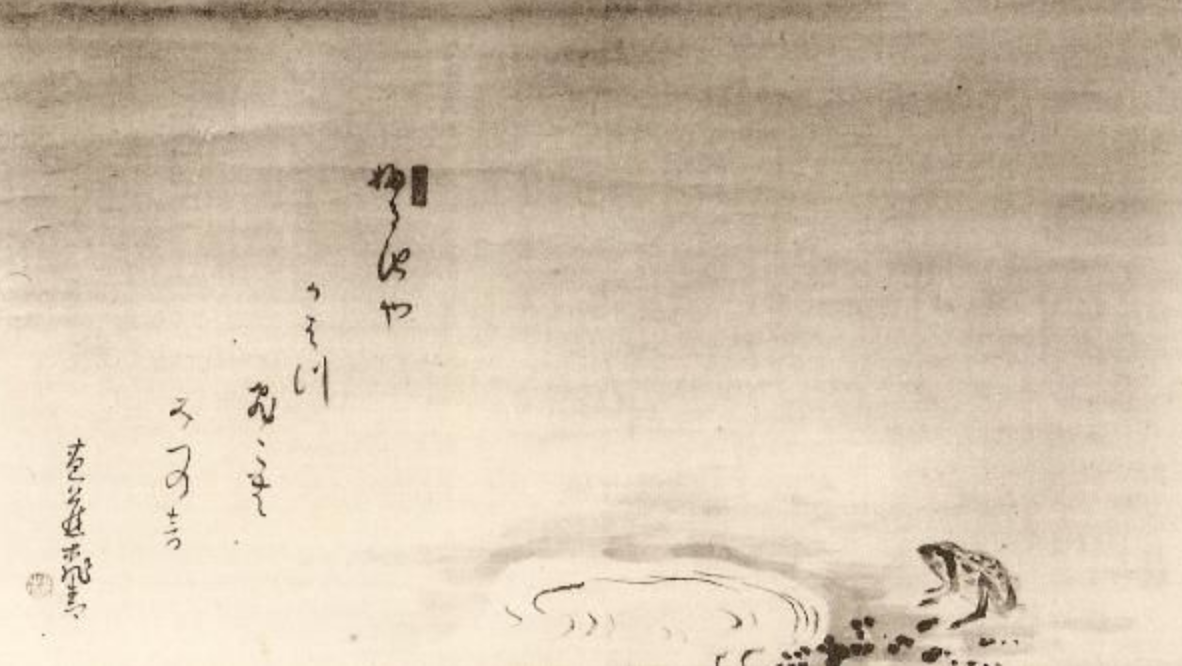

So, well, that's a big question to start to unpack. Let's start with the global. I think that simply because what is very clear is that those of us in the Anglophone world, we bluntly do not read enough poetry outside of the British American tradition because we do not read enough poetry in translation, but that's frankly, part of the wider problem that we don't read enough literature in translation full-stop.

And so you know that there are tremendous poets working in languages other than English that never reach the readership, even amongst poets that they deserve, just simply because they haven't yet been translated into English and the barriers and the bottlenecks that there are to do that. But absolutely, you know, my writing of poetry has got better by attempting to read more poets outside of English in translation. And also tentatively trying translations as well, you know because that is a very, very good discipline to actually discover more work and discover more artists. So, yes, absolutely, there is a whole sea of poets out there who one is not familiar with.

In a specific UK context, there has been, I think up until about 10, 15 years ago, there had been a big lacuna, which was the poets of colour, writers of colour had effectively been overlooked in telling the story of poetry in the British Isles, but basically, writers of colour had not even been written out, just not been considered. And so, yeah, that has changed, that is changing. And we're starting to see the fruits of a lot of work by writers and activists before, in pushing people forward in developing and bringing more voices to readers, you know, broader audiences and winning the TSA prize last year and like a book, winning the Ford for last year as well for her best single poem. But that's the tip of what has been a 20, 25-year project to actually start to say to the wider British poetry establishment. There is a whole thriving set of poetries and poetics that are out there that you are not yet fully recognizing. And that is changing, there is still plenty of work to be done, but it is getting there and getting better. And I think bluntly, you cannot tell a credible story about the history of British poetry now without recognizing that large scene that writers of colour have provided since the 1950s and sixties onwards, especially.

Ben Yeoh:

Yeah, I think I agree with all of that. It was quite a while back now, but I remember first discovering ghazals and Sufi poetry. And, you know, this tradition, which stretches back so far has a performance element to it, followed by, you know, millions of people, right. But outside of the English language or visual poetry, you can't look at any of those original haikus or written in Chinese or Japanese poetry and not say, well, wasn't that visual poetry before we in the Anglophone world would have even thought about visual poetry. So I think that's on global and obviously the British poetry, true. So I guess you could argue poetry is one of humankind's oldest art forms and considering, Oh, oral poetry, there's an argument that maybe it's his oldest art form, and maybe you've had some version of the Insta poet every two years ever since the start of that. There were some arguments that I guess that it's one of the smallest art forms that at least in its elite form has this niche readership. I mean, what do you make of that? Or maybe the converse is perhaps if you consider rap as poetry, there is not that. And I was reading one opinion that argued that the advent of rap and hip hop, and to some extent, those forms of art was the reaction of black artists or artists of colour finding essentially a poetry expression, but in a different form. So I'd be interested in seeing, like, do you think is one of the oldest art forms is poetry really small today or is that perhaps it's more diffuse if you think about it in terms of a larger art form.

Rishi Dastidar:

Yes. I tend towards the latter. And again, I think, to some degree, that question comes out of effectively post hyphen modern inheritance in the sense that what you see from the 1920s onwards, is effectively poetry becoming more and more elite than it had been up until that moment. And this is not to deny the power of the art that comes out from that period of post-first world war onwards. But there is absolutely an inflexion point that you can detect that where our data even further back than the beginning of hip hop, actually to the moment which pop music, rock and roll moves out of the music hall and moves into something that looks much more like wider society. And there's an absolute, absolute crossover point. So there's certainly [Inaudible 13:16] British poetry where you have that happening and you have the rise of the movement, so the last, obviously white male movement of British poet. And gradually you see pop music, almost taking that space that poetry once had, and you see poetry running more to the Academy, running more to art school thinking art school theories, and meanwhile, people's hunger and desire for music and speech and song is being satisfied through pop music as well.

So poetry in its broad sense is still there, it's present, it's around, it diffuses an absolutely brilliant word to actually describe it because we know it's there in songs. We know it's there in adverts around us. We know it's in hip hop and rap, but the elite pursuit that we call poetry, yes, it's by definition has got a lot smaller. But I think one of the things that isn't often a compliment to the point is that now, it's not more in terms of thinking in terms of attitudes with what you might describe actively more than this post-modernist visual arts movements and visual arts thinking. And of course, that's where a lot of critical attention and cultural elite cultural formation attention is paid. And so you have this weird dichotomy where have people who call this thing called poetry and because it's practice by very few people, they give off the impression that, of course, it's a very elite pursuit, but then you actually stop and think about it in that poetry is a lot wider and it's a lot bigger and there's a lot more of it around.

Ben Yeoh:

Yes, great. I think I agree with all of that as well. So I like lists, you like list, Saffron Jack essentially started with a list and continues with list. What's up with lists? Should we be interested in list poetry? Why do you like lists so much?

Rishi Dastidar:

List poetry, yes. I mean, list poetry, list poems, not quite as a genre of poetry in their own right. But do they exist as a thing that's recognizable? Yes. Do I write a lot of them as well? Yes. As a sidebar a review does stick in my mind of my first book where I did said it's hard to [Inaudible], can't really disagree with that. Lists are wonderfully powerful because they are orders, they are a tool of making sense of the world. They are the ultimate weapon if you are a control freak who feels that they are out of control. Just by the very act of putting something down in some sort of order, you're suddenly making a claim against kales, suddenly making a claim against entropy almost, in terms of, I, for this moment can [Inaudible] this moment in time and actually grasp things and put them together in a way that starts to approximate sense, approximate logic, approximate flow. And so I think that's why they have their appeal more than everything else. And especially in times and in situations where you feel on the edge of chaos and you feel things spiralling out of control, there's nothing more powerful, but reasserting that control through doing that. And you know, if you think of a fundamental level, what the poets do, we're observers as much as we're anything else. So poems are bluntly lists of images, lists of sensations, lists of memories that we're refound, recontextualize, reasserted. And some of us are better than others at fundamentally disguising that they are lists. I am particularly bad at not disclosing them.

Ben Yeoh:

So Saffron Jack is a long-form poem. Some of humanity's greatest artworks have been long-form poems, but I think arguably today, the long-form poems have gone, yours excluded, there's very few of them. Where have they all gone? Should we be bringing them back?

Rishi Dastidar:

They haven't gone. What has happened is that the publishing industry prefers to call them something else because they might be more salable in different ways. I could point you towards Robin Robertson's Booker prize-nominated novel, The Long Take. It's written in verse. It doesn't necessarily have…

Ben Yeoh:

It's not a novel it's a long-form poem…

Rishi Dastidar:

It doesn't have anything that you might recognize as traditional prose characterization. It doesn't do much by way of plot. And when you look at the way that it's arranged on the page, lots of white space between lines. Why is it called a novel? [inaudible] one of our great poets and editors. But presumably, someone somewhere had a commercial discussion around, you know, what if we positioned this as a novel, we're far more likely to have success than the…

Ben Yeoh:

Bigger market for novels.

Rishi Dastidar:

Is bluntly the case. I mean, sort of knowing your field, [inaudbile] lots of interesting monologues, the opposition to those monologues, but then when you actually break them down and look at what they're doing on the page, they're poems as well, and they flow through and they have poetic effects as well. But just because they happened to be delivered by one person standing on a stage, and they've been published by a Mathew Ramika, we call them a play, we call them a monologue instead of a poem. You know, I mean, again, this comes back to the idea of poetry being diffuse and it's very diffused and this means it's harder to actually see where it is actually a poem in disguise to something that's more commercially palatable.

Ben Yeoh:

It's become like one of those symbiotic creatures, which has just squirrelled its way and all sorts of other art forms to audit survival because you don't name it. Speaking about saffron Jack, long-form poem, ideas, do you think there was just one major idea flowing through Saffron Jack? Was that how you kind of thought about it or came about or is it kind of a lot of mini ideas, which kind of coalesced? Talk me through how you kind of thinking about the themes and what saffron Jack's about.

Rishi Dastidar:

Definitely the former. The poem is an attempt to try and answer the question, what would it be like to set up your own country, call yourself King of your own country? And I know that [ ] a lot of megalomania on my part, but for a long time, I've been fascinated by these things called micronations. So places like Sealand, even San Marina, these places which look too small to be viable countries, and yet they call themselves countries. And when you look at micronations, in particular, there's always something interesting going on in terms of why someone just decided that they could be American and Australian, but they can't move to or immigrate to a different country.

So instead they decide that they must set up their own principality and do so in a backyard or in Sealand's case, in this [ ] The sort of person who finds themselves feeling that atoms being rearranged just by the pattern of words on a page, by the sound of words hitting the air. Chances are you're going to like poetry and you will find poets types of poetry that work for you. And I am absolutely a high mantra of poetry. I don't care whether, what turns you on is the absolute avant-garde language gains of JH Prin or whether it is, you know, Ruby Cow and other Insta poets. I am just happy that you are now in the world of poetry and enjoy it enough. You will start to find lots of other people who have that similar atom rendering, atom changing effect on you. If you're moved enough by that experience to start to want to produce it and create it yourself, the fundamental thing you must do is read, read, read, read, read, read. And you will find that the more you read the better you get at writing poetry.

Because it's only by reading that you actually discover what you like, what you don't like, what is possible on a page, what isn't possible on the page. And something that people who had just been setting out often say is, oh, but if I read too much then I'm going to end up sounding like those poets. And that's a necessary stage of any artistic evolution. Any writer who's published goes through a phase of sounding like their heroes, sounding like their idols. The trick is you have to push through that phase to actually start to get to a place where you start to sound like you and you start to sound like your voice, your obsessions, and things that are really animating you. And that can be a long process. Absolutely. My friend, Joe Bell talks about the fact that becoming a poet takes something like 10 years of reading and writing and dedicating yourself to it, which means... And knowing what we talked about at the top in terms of the lack of rewards. And that need for having an income outside of poetry means that it's a vocation and it's something that you have to really want to do outside of thinking, I'm going to write a bestseller because chances are, you're not. And so, that tends to winnow people out a bit that tends to leave the people who are obsessive stroke dedicated. But, honest to goodness, don't be scared. Don't be scared of coming into this world. Don't think that poetry isn't a thing for you, don't think that you're going to be asked, ahh, yes but what is the subtext of what you are saying of what you are writing every time? Because that's only a question of concern to people teaching English. Poets don't ask you about subtext. Poets don't care

Ben Yeoh:

Yeah. And even established poets writers, we all worry. Like, do we really have a voice? Does this sound like X or Y? I mean, in some ways these are kind of concerns which never go away if you are a reader and a writer.

Rishi Dastidar:

Exactly, exactly so.

Ben Yeoh:

Any newsletters, pamphlets, or magazines that maybe people want to get into, we should look at, in fact, so I hadn't even prepared this. Look, I have one (Inaudible) it’s coming on screen now. I have a business day job. But keep poetry around for me because you never know when that might help. So obviously that's what I would recommend. And obviously, you're linked with them. So that's a bit of a bias one. So if there's any other, so Realto, we'll put that in the links actually, we'll have something

Rishi Dastidar:

So there's plenty of places that you can go to, to start to discover the world of poetry. I mean, the poetry society is the most obvious sort of initial starting point. It is the UK's dedicated member organization for poetry, for the promotion of poetry as well. They publish the poetry review, the UK's leading journal. And so taking a subscription out to that gives you an immediate sense of what is going on now in contemporary British poetry. Then also it gives you a sense of the spread of activities and aesthetics that people are interested in. Purchase also help organize a whole raft of writing groups around the country. So if you want to become more active, that is absolutely a place to go. Hopefully, reopening soon, I should say is the national poetry library at the South bank. And it is the UK's main library for poetry. And you'll be able to get from the most collections that have been published since 1950 onwards and all the latest additions of the magazines. And for those of you outside of London, Leeds has a very good poker library in the university managed still. I think its poetry library is about to open soon as well. So those are well worth checking out.

If you're moved enough to actually want to start writing, then do check out the poetry school, the UK's main provider of poetry education. Plenty of courses at all levels, beginner, intermediate, advanced taught by poets and many poets I should say, who are writing now, they got their starts by doing school courses. I was one, I spent a lot of my formative years writing as many poetry school courses as I could get my hands on while I'm still learning, but while I was doing that. And yeah, the realtor, as well as you know, I am biased because I'm a contributing editor then, but three times a year we give you a very good sense of what's going on in terms of British and international contemporary poetry. So yeah, plenty to choose from there. And of course, like we've been saying all the way through in terms of poetry is the fierceness. You will hear poetry on the radio, poetry places, a great vehicle for finding stuff out. Gal jet Nagra on radio four extra has a regular slot where he digs into the BBC's archives and brings us more poetry bits and pieces like that as well. And of course, social media, like we said, at the start, you will find poetry on Insta poems or poetry on Instagram. Go there, look at that. There's plenty of poetry on Twitter as well. Go there, have a look there, plenty going on.

Ben Yeoh:

Great. Yeah. Twitter poetry is a great happenstance thing I've found. So I actually, this, I guess, turned out to be one of the themes of our chat is the fact that poetry is much more alive in the world and in our lives than we might think. But I had a question here about what we thought the social function of poetry is. So that kind of brings it all together that do you think it has a social function? I guess we're going to be arguing, yes, but I'd be interested to see what you think it is, what does poetry do for us?

Rishi Dastidar:

So, and I think it's something that people have been coming back to more, especially over the last 10, 15 years as it's felt that more of our working lives and professional lives have started to get more regimented and more prescribed and more broken up and most of us, especially working on white-collar jobs are in a world of targets and fairly abstracted PRI bloodless language. I don't think it's an accident, but there's all of that going on. People are hankering for something that is a lot wilder and a lot more untrammelled and a lot freer of those sorts of constraints. So I think there's that. I think the wider social role of poetry as a space to actually say things which it is hard to say in pros, to acknowledge vulnerability, to acknowledge pain, to actually articulate emotions, memories, sensations, which if you put them in pros, would be so harrowing and so gleeful that people wouldn't want to engage with that. But by making them poems, people can come in at the site and start to engage almost in a more safe way as well. And so start to open up those things.

So poetry is a form of witness, I think is absolutely vital, poetry as a way for overlooked, unheard voices from unheard communities is another thing as well. You know, claiming space that might not otherwise be achieved through more rational means of persuasion. I think there are all those functions that are there as well. I mean not to recycle Shelly's legislators' line but poets have a role in terms of dreaming of what future scenarios future states might be... Oh, and Pointing to suggesting the weird gaps and abstractions in language, you know, the gap between rhetoric and the truth on the ground. Most good poets that you ever meet, are acutely interested and are acute to those wild gaps between what are corporation claims and what they actually do, what a politician claims and what they actually do, that as well. Poets as canaries in languages [ ]

Ben Yeoh:

Yeah. I think that's a very coherent argument for the vitality of poetry and its function today kind of never more important and maybe never more alive. I hadn't quite thought about it like that. So yes, for sure. Great.

Rishi Dastidar:

One more point. I was just going to add one more point to that as well in that, yeah, If you think about the internet being such a text-driven medium, you think hypertext markup language is what it is and yeah, we read so many web pages. Twitter is a text-driven medium, as much as it is anything else. It is therefore unsurprising that the oldest form of putting words together, which is poetry, suddenly has a renascence as well. We're living in a much more language-driven age. So the oldest form of putting language together, having a [ ] I think those are absolutely connected

Ben Yeoh:

Instagram tried to get in there with their visuals, but actually visual poets got all over that as well. So yes, and actually audio because even in the audio thing, you've got this clubhouse and all of that. Going back even further or the oral poetry and all the rhetoric and stuff, so yeah. Poetry, the original social media. So coming to our last, I guess a couple of questions here, what I'm going to put on one of your other hats which is your copywriting hat, I guess, and how that links. So I didn't really know there was such a thing as brand language. So I'm interested in that. And I didn't know that there were grammar memes either, and I didn't know that verb should be a superpower. So I don't know whether you want to comment on grammar means brand language, verbs as a superpower and what the world of copywriting has to say about the world.

Rishi Dastidar:

Right. So I have lots of views on lots of those. The grammar memes I think is probably, so let's recast it this way. When you look at an average day on Twitter and you look at lots of memes flying around, how do they actually work? Why do they actually work? It's because they're fucking around with syntax, to put it crudely, they're doing something interesting with syntax that just jolts you out of your comfortable reading. And so that's the property that suddenly makes them [ ] so that's yeah, exactly. It's a poetic effect. Brand language, I think commercially in corporate land, we're very familiar with the idea that a logo of visual identity is something that all organizations should have as a means of carving out some sort of unique distinction, unique visual distinction. Brand language is an attempt to do that verbally for the language that an organization might use in written communications and in spoken communications as well. Now, is it a lot harder to cast something out that is unique and distinctive through language? Yes. But at the same time, I can say to you, for example, if I sent you an email so how D Ben, this is John Lewis polymer. You would know instantly, hang on. That's not right. That's not how John Lewis speaks. As it was John Lewis you would expect them to say, dear Mr Yo, hello, how are you?

And that's all brand language is. It's finding the way or the particular vocabulary, but also the grammar and syntax that actually starts to make that organization's personality come to life. And you can geek out on that sort of stuff as much or as little as you want. But when you start to look at that world, you see those organizations with stronger, better, more creative brands have given as much thought to the words part of the communication as much as they do to the design and the art direction part of the communications as well. And this is why there is absolutely a cross over between copywriting and poetry as well. I presented a documentary for radio four last year, which investigated those links between advertising and copywriting and how you can find lots of poets tucked away in advertising. And again, to bring us back, right now there's a moment where brands are using poets as a means of their interest as a means of actually communicating sincerity and death. But also it points to the fact that we are, again, poetry is diffuse. If the commercial world is using poems, it's there for a reason.

Ben Yeoh:

We should definitely write to Nike and say, the chief poetry officer, we've got one here. And verbs as a superpower. Do we not pay enough attention to our verbs?

Rishi Dastidar:

Yeah, we definitely don't pay enough attention to verbs. And if you want a quick tip to improve your writing, no matter what you're writing, it's to use more verbs. And I think people don't because they're doing words and subconsciously that means that they know that they're on the hook to actually do things, rather than be obstructed away in various other verbiages. But if you're struggling, just actually, what happens when I change a verb, what happens when I use a different verb and you'll suddenly start to see whatever it is that you're writing, lift and change.

Ben Yeoh:

Great. Okay. And so coming to our final question, which is what does being productive look like for Rishi? What does a good poetry writing day look like? Well, it could be a good copywriting day as well. I don't know if you mix and match the two days as well, but maybe if you've got a good poetry writing day, you know, does it include running as a food, everything, what does your very best day look like?

Rishi Dastidar:

My very best day? I mean, I don't think I have separate copywriting and poetry days because my style as a writer is to get first drafts out very, very quickly and then continually work on them as we go. And so poems, especially are things that arrive in-between times. And in that space between meetings in that half-hour between briefs or something like that. So it's rare that I have a special day where this is a poetry day. But a good day, a productive day probably features a run at the beginning of the day, hopefully, features a decent breakfast. And then hopefully at my desk by nine and maybe one meeting, maybe no meetings and a relatively quiet on slack and email. So I can just actually knock around for a couple of hours

Ben Yeoh:

Does that involve reading as well? Would you read a bit, does that help the writing? And there was one person, I can't remember who, who said a good writing day actually starts with the first half of the day as reading, again, in an ideal world.

Rishi Dastidar:

No, so for me, I know that my productivity dips after lunch. So after two o'clock is going to be reading, admin and that sort of hopefully subconscious, deeper thinking. Rare is the good thing for me that emerges after two o'clock. It does sometimes, but generally speaking, I find better words in the morning.

Ben Yeoh:

Sure. And do you have a... In the previous place, was that your writing desk, do you have a writing desk or? I kind of know that actually, cause I've seen it on Twitter poems because they will hit you anywhere, you know, little phone poems done on like whatever notes or stuff around is also a favourite kind of medium, but I guess you'll get back to your writing desk and transcribe it if you can.

Rishi Dastidar:

Yeah. I mean, I've written first drafts on tops of buses. I've written first drafts on tubes. I wrote most of the title poem for Ticker Tape on a journey from our front hole on a bus, on a tube, in the foyer of a cinema, in the cinema seat and then all the way back as well. So they can arrive anywhere. But at some point, there has to be some sort of consolidation and that has to happen at the desk. So even if the act of creation isn't happening at the desk, the act of moving into production, that has to happen there.

Definitely.

Ben Yeoh:

Great. Okay. Well, thank you so much for this conversation. I learned a lot and maybe quite thoughtful about poetry in the world today. Please do check out Rishi's books, which we'll have links to. And if you're interested in finding out about poetry, I think our theme is just do it, please do it.

Rishi Dastidar:

Absolutely. Thank you, Ben.

Ben Yeoh:

Great. Thanks.