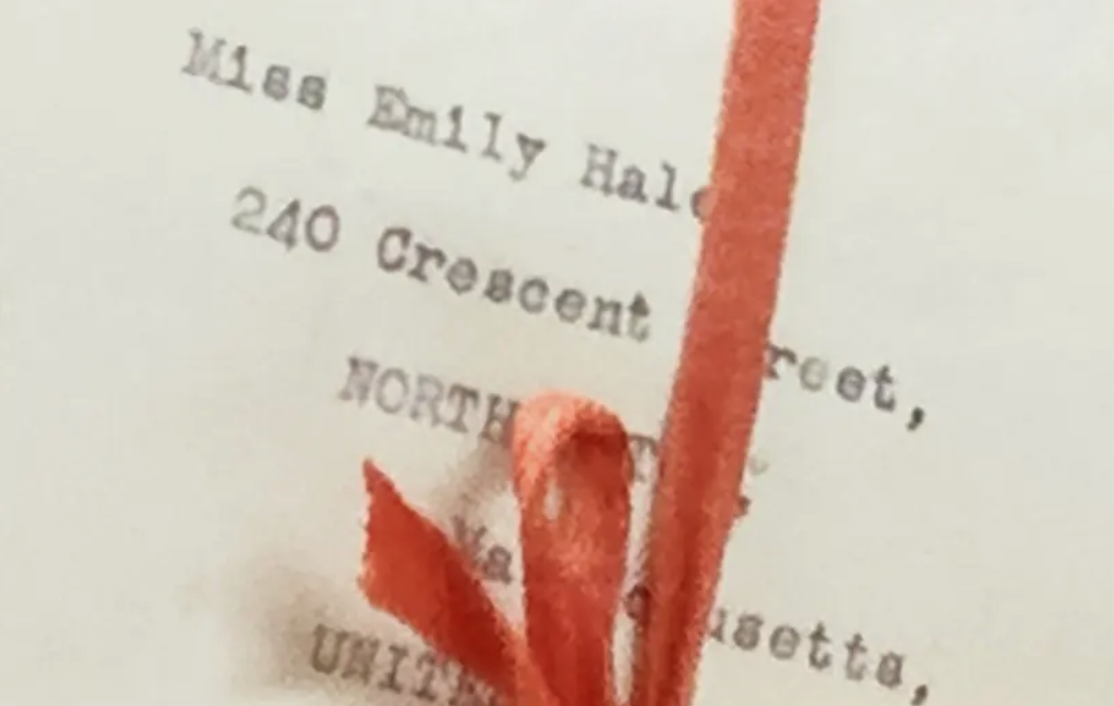

The love letters of TS Eliot to Emily Hale (likely inspiration for many of his famous poems) have been revealed (around Jan 2020), 50 years since Hale’s passing.

Eliot wrote a statement - more a letter - to accompany the letters, whenever they were to be unveiled. The letter goes:

“It is painful for me to have to write the following lines. I cannot conceive of writing my autobiography. It seems to me that those who can do so are those who have led purely public and exterior lives, or those who can successfully conceal from themselves what they prefer not to know about themselves – there may be a few persons who can write about themselves because they are truly blameless and innocent. In my experience, there is much for which one cannot find words even in the confessional; much which springs from weakness, irresolution and timidity, from petty self-centredness rather than from inclination towards evil or cruelty, from error rather than ill-nature. I shall be as brief as I can.

During the course of my correspondence with Emily Hale, between 1932 and 1947, I liked to think that my letters to her would be preserved and made public after we were dead – fifty years after. I was however, disagreeably surprised when she informed me that she was handing the letters over to Princeton University during our lifetime – actually in the year 1956. She took this step, it is true, before she knew that I was going to get married. Nevertheless, it seemed to me that her disposing of the letters in that way at that time threw some light upon the kind of interest which she took, or had come to take, in these letters. The Aspern Papers in reverse.

I fell in love with Emily Hale in 1912, when I was in the Harvard Graduate School. Before I left for Germany and England in 1914 I told her that I was in love with her. I have no reason to believe, from the way in which this declaration was received, that my feelings were returned, in any degree whatever. We exchanged a few letters, on a purely friendly basis, while I was up at Oxford during 1914-15.

To explain my sudden marriage to Vivienne Haigh-Wood would require a good many words, and yet the explanation would probably remain unintelligible. I was still, as I came to believe a year later, in love with Miss Hale. I cannot however make even that assertion with any confidence: it may have been merely my reaction against my misery with Vivienne and desire to revert to an earlier situation. I was very immature for my age, very timid, very inexperienced. And I had a gnawing doubt, which I could not altogether conceal from myself, about my choice of a profession – that of a university teacher of philosophy. I had had three years in the Harvard Graduate School, at my father’s expense, preparing to take my Doctorate in Philosophy: after which I should have found a post somewhere in a college or university. Yet my heart was not in this study, nor had I any confidence in my ability to distinguish myself in this profession. I must still have yearned to write poetry. For three years I had written only one fragment, which was bad (it is, alas, preserved at Harvard). Then in 1914 Conrad Aiken showed Prufrock to Ezra Pound. My meeting with Pound changed my life. He was enthusiastic about my poems, and gave me such praise and encouragement as I had long since ceased to hope for. I was happier in England, even in wartime, than I had been in America: Pound urged me to stay in England and encouraged me to write verse again. I think that all I wanted of Vivienne was a flirtation or a mild affair: I was too shy and unpractised to achieve either with anybody. I believe that I came to persuade myself that I was in love with her simply because I wanted to burn my boats and commit myself to staying in England. And she persuaded herself (also under the influence of Pound) that she would save the poet by keeping him in England. To her, the marriage brought no happiness: the last seven years of her life were spent in a mental home. To me, it brought the state of mind out of which came The Waste Land. And it saved me from marrying Emily Hale.

Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me; Vivienne nearly was the death of me, but she kept the poet alive. In retrospect, the nightmare agony of my seventeen years with Vivienne seems to me preferable to the dull misery of the mediocre teacher of philosophy which would have been the alternative.

For years I was a divided man (just as, in a different way, I had been a divided man in the years 1911-1915). In 1932 I was appointed Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard for one year; and even Vivienne’s mother agreed that it was out of the question for Vivienne to go to America with me. I saw Emily Hale in California (where she was teaching in a girls’ college) early in 1933, and I saw her from time to time every summer, I think from 1934 on, as she always joined her aunt and uncle who took a house every summer at Chipping Campden.

Upon the death of Vivienne in the winter of 1947, I suddenly realised that I was not in love with Emily Hale. Gradually I came to see that I had been in love only with a memory, with the memory of the experience of having been in love with her in my youth. Had I met any woman I could have fallen in love with, during the years when Vivienne and I were together, this would no doubt have become evident to me. From 1947 on, I realised more and more how little Emily Hale and I had in common. I had already observed that she was not a lover of poetry, certainly that she was not much interested in my poetry; I had already been worried by what seemed to me evidence of insensitiveness and bad taste. It may be too harsh, to think that what she liked was my reputation rather than my work. She may have loved me according to her capacity for love; yet I think that her uncle’s opinion’s (her uncle by marriage, a dear old man, but wooly-minded) meant more to her than mine. (She was fond of her uncle John but did not get on very well with her Aunt Edith). I could never make her understand that it was improper for her, a Unitarian, to communicate in an Anglican church: the fact that it shocked me that she should do so made no impression upon her. I cannot help thinking that if she had truly loved me she would have respected my feelings if not my theology. She adopted a similar attitude with regard to the Christian and Catholic view of divorce.

I might mention at this point that I never at any time had any sexual relations with Emily Hale.

So long as Vivienne was alive I was able to deceive myself. To face the truth fully, about my feelings towards Emily Hale, after Vivienne’s death, was a shock from which I recovered only slowly. But I came to see that my love for Emily was the love of a ghost for a ghost, and that the letters I had been writing to her were the letters of an hallucinated man, a man vainly trying to pretend to himself that he was the same man that he had been in 1914.

It would have been a still greater mistake to have married Emily than it was to marry Vivienne Haigh-Wood. I can imagine the sort of man each should have married – different from each other, but also very different from me. It is only within the last few years that I have known what it was to love a woman who truly, selflessly and whole-heartedly loves me. I find it hard to believe that the equal of Valerie ever has been or will be again; I cannot believe that there has ever been a woman with whom I could have felt so completely at one as with Valerie. The world with my beloved wife Valerie has been a good world such as I have never known before. At the age of 68 the world was transformed for me, and I was transformed by Valerie.

May we all rest in peace“ (Source TS Eliot Foundation)

Scholars think these lines in the Four Quartets may have been about Emily Hale:

“What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened

Into the rose-garden. My words echo

Thus, in your mind.”

In his letters he wrote to Hale:

“You have made me perfectly happy: that is, happier than I have ever been in my life; the only kind of happiness now possible for the rest of my life is now with me; and though it is the kind of happiness which is identical with my deepest loss and sorrow, it is a kind of supernatural ecstasy.”

In the end, he didn’t marry Hale after his first wife died. He married Valerie.

And, no one exactly knows why. All Eliot wrote:

“Emily Hale would have killed the poet in me; Vivienne nearly was the death of me, but she kept the poet alive.”

Poetry as mysterious as poets as people as love as everyone else.